Absolute vs. Relative Risk Calculator

Understand Your Drug Risk

This calculator helps you see how absolute risk differs from relative risk when evaluating drug benefits or side effects. Enter the baseline risk and the drug's effect to see what the numbers really mean for you.

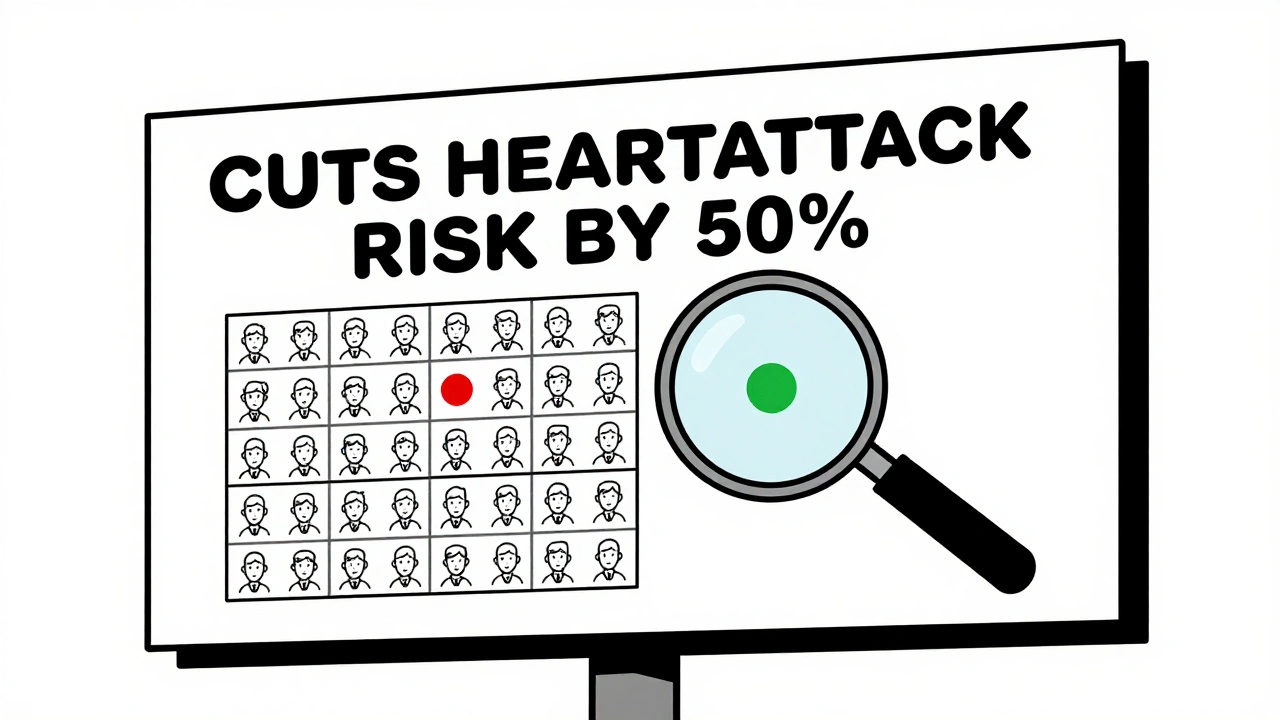

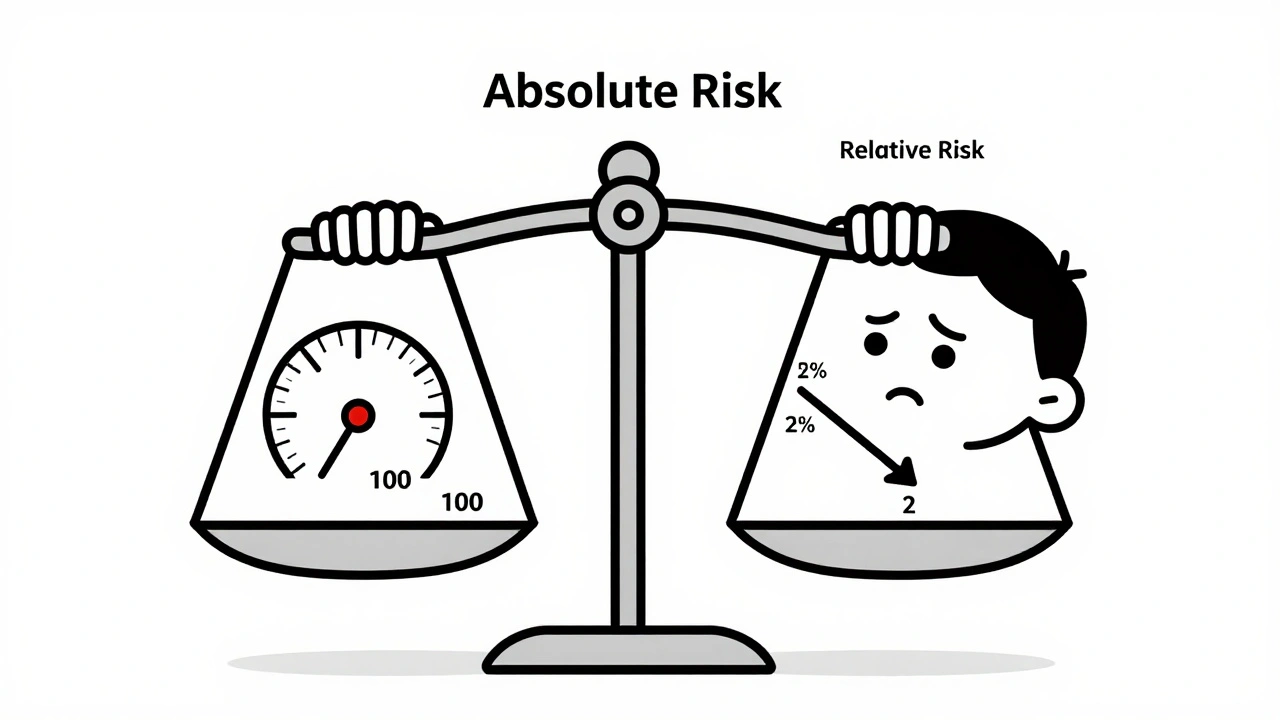

When a drug ad says it "cuts your risk of heart attack in half," you might think you’re avoiding a 50% chance of having one. But what if your actual risk was only 2% to begin with? After taking the drug, it drops to 1%. That’s not a 50% chance avoided - it’s a 1 percentage point change. This gap between absolute risk and relative risk is why so many people misunderstand drug benefits and side effects - and why doctors, regulators, and patients are finally pushing back.

What Absolute Risk Really Means

Absolute risk tells you the actual chance something will happen to you. It’s simple: out of 100 people like you, how many will experience the side effect? Or how many will avoid a heart attack? It’s measured in real numbers - percentages, per 1,000, or per 100,000.For example, if 1 in 10,000 people who take a certain blood pressure drug develop a rare liver issue, that’s an absolute risk of 0.01%. If 5 out of 100 people on a statin report muscle pain, that’s a 5% absolute risk. These numbers don’t lie. They’re grounded in your real-world experience.

Doctors and regulators use absolute risk to decide who actually benefits from a drug. If only 1 in 1,000 people gain a meaningful benefit, and 1 in 50 get a side effect, the math says: this drug isn’t for everyone. It’s also why the FDA now recommends absolute risk be shown first in patient materials. Because if you’re trying to decide whether to take a pill for the next 10 years, you need to know: what’s the actual cost to me?

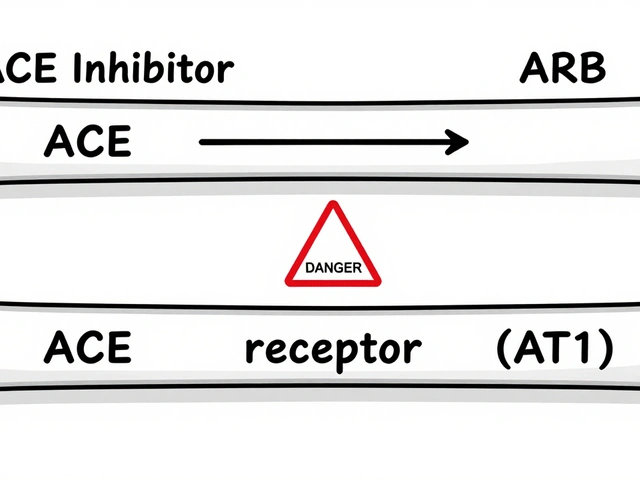

How Relative Risk Can Be Misleading

Relative risk compares two groups - say, people who took the drug versus those who didn’t. It’s a ratio. If the drug reduces heart attacks from 2% to 1%, the relative risk reduction is 50%. That sounds impressive. But here’s the trick: it doesn’t tell you the starting point.That same 50% relative reduction could mean:

- From 2% to 1% (1 in 100 → 1 in 200) - a small real-world change

- From 50% to 25% (1 in 2 → 1 in 4) - a massive, life-saving drop

Pharmaceutical ads love relative risk because it makes small benefits look huge. A drug that reduces the risk of a rare side effect from 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 1,000,000 sounds like a 90% improvement. But in absolute terms, you’re going from 0.001% to 0.0001% - a 0.0009% change. That’s not meaningful for most people.

One study found 78% of U.S. direct-to-consumer drug ads used relative risk reduction without ever mentioning the baseline risk. Patients walked away thinking they were getting a dramatic benefit - when in reality, their odds barely budged.

Why Both Numbers Matter

You can’t understand a drug’s true impact by looking at just one number. Absolute risk tells you what’s likely to happen to you. Relative risk tells you how much better (or worse) the drug makes things compared to nothing.Take venlafaxine, an antidepressant. Studies show 20% of people on it report sexual side effects. On placebo, it’s 8.3%. The relative risk is 2.41 - meaning you’re 2.4 times more likely to have this side effect. Sounds scary. But the absolute difference? Just 11.7 percentage points. That’s 1 in 8.5 people. For some, that’s a dealbreaker. For others, it’s worth it to feel better.

Same goes for statins. If you’re a 60-year-old man with high cholesterol and no heart disease, your 10-year risk of a heart attack might be 10%. A statin might lower that to 8%. That’s a 20% relative risk reduction - but only a 2 percentage point absolute drop. For someone with a 2% baseline risk, that same statin cuts it to 1.6% - a 20% relative drop again, but now it’s just 0.4 percentage points. Is that worth daily pills and potential muscle pain? The answer depends on the absolute numbers.

How to Spot the Trap

Here’s how to cut through the noise:- Find the baseline. What’s the risk without the drug? If it’s not stated, ask. A 50% reduction means nothing if you don’t know what you’re reducing.

- Look for absolute numbers. If the ad says "reduces risk by 50%," check the small print for "from X% to Y%." If it’s not there, assume the benefit is small.

- Ask for the Number Needed to Treat (NNT). This tells you how many people need to take the drug for one person to benefit. An NNT of 100 means 99 people take it for no benefit - just one person avoids a bad outcome. That’s not a miracle drug. That’s a gamble.

- Watch for time frames. "Reduces heart attack risk by 30%" - over 5 years? 10 years? A 30% drop over 10 years is very different from 30% over 1 year.

One patient I spoke with refused a cholesterol drug because she read it "reduced heart attacks by 40%" - until I showed her her personal risk was 1.5%, and the drug lowered it to 0.9%. "That’s not 40% of me having a heart attack," she said. "That’s 1 in 100 becoming 1 in 167. I’m not taking a pill for that." She was right.

What the Experts Say

Dr. Steve Woloshin and Dr. Lisa Schwartz from Dartmouth have spent decades studying how medical numbers are presented. Their research found that only 8% of patients can correctly interpret relative risk alone. But when absolute risk is shown with simple visuals - like a grid of 100 people with colored dots for who gets affected - 62% understand it.They recommend this simple script:

- "Without the drug, about X out of 100 people like you will have this problem."

- "With the drug, that number drops to Y out of 100."

- "So, the drug helps Z out of 100 people."

That’s it. No percentages, no ratios - just people. That’s how humans think.

Side Effects Are Treated the Same Way

The same math applies to side effects. A drug might increase the risk of depression by 50% - but if the baseline risk is 2%, it only goes up to 3%. That’s a 1 percentage point increase. For someone with no history of depression, that’s not a red flag. For someone already struggling? It’s a serious concern.Pharmaceutical companies know this. They use relative risk to scare you about side effects when they want to downplay them. But when they want to sell the drug, they use relative risk to make the benefit sound massive. It’s the same tool, flipped.

That’s why the European Medicines Agency now requires both absolute and relative risk in patient leaflets. The U.S. FDA is catching up - but enforcement is still weak. Until then, you have to be the one to ask: "What does this actually mean for me?"

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be a statistician. But you do need to ask the right questions before you take any new medication:- "What’s my risk of this problem without the drug?"

- "How many people like me actually benefit?"

- "What’s the real chance I’ll get a side effect?"

- "Is this benefit worth the daily pill, cost, and possible side effects?"

Bring a printed copy of the drug’s fact sheet. Ask your doctor to show you the numbers in plain terms. If they can’t or won’t, that’s a red flag. Good care isn’t about selling you a pill - it’s about helping you understand your choices.

Medicine is full of numbers. But your health isn’t a math problem. It’s a personal decision. And you deserve to make it with real information - not inflated percentages.

What’s the difference between absolute risk and relative risk?

Absolute risk is the actual chance of something happening to you - like a 5% chance of getting a side effect. Relative risk compares that chance to someone not taking the drug - like saying the risk is doubled or cut in half. Absolute risk tells you what’s likely to happen to you. Relative risk tells you how much better or worse the drug makes things compared to nothing.

Why do drug ads always say "reduces risk by 50%"?

Because it sounds better. If your heart attack risk drops from 2% to 1%, the absolute change is tiny - just 1 percentage point. But the relative reduction is 50%. Ads use the bigger number to grab attention. That’s not deception - it’s marketing. But it’s misleading if you don’t know the baseline.

How do I know if a drug’s benefit is real or just hype?

Look for the Number Needed to Treat (NNT). If the NNT is 10, it means 10 people need to take the drug for one person to benefit. If the NNT is 100, 99 people take it for no benefit. Also, ask for the absolute risk reduction - not just the percentage. A drug that cuts your risk from 1% to 0.8% isn’t life-changing - it’s barely noticeable.

Can relative risk ever be useful?

Yes - but only when you know the baseline. Relative risk helps researchers compare how a drug works across different populations. For example, if a drug cuts heart attack risk by 30% in both high-risk and low-risk groups, it’s working consistently. But for you as a patient, absolute risk tells you whether it matters for your life.

What should I ask my doctor about side effects?

Ask: "What’s the chance I’ll get this side effect?" Not "How much does it increase the risk?" Then ask: "Compared to someone not taking this drug, how many more people like me will have this problem?" That’s the absolute difference. And ask: "Is this side effect common, rare, or serious?" Sometimes a 5% chance is worth it. Other times, it’s not.

What Comes Next

If you’re still unsure after checking the numbers, don’t rush. Ask for a second opinion. Look up the drug on the FDA or EMA website - they list clinical trial data. Talk to a pharmacist. They’re trained to read the fine print.And if you’re on a drug and feel like you were misled - you’re not alone. Millions of people have been. But now you know how to spot it. And next time, you’ll ask the right questions.

Billy Schimmel

So let me get this straight - if I’m a 60-year-old guy with a 2% chance of a heart attack, and a pill cuts it to 1%, I’m supposed to be thrilled because it’s ‘50% better’? Nah. That’s like saying you cut your risk of stepping on a Lego in half - from 1 in 100 to 1 in 200. I still ain’t gonna walk barefoot in the living room.

Pharma’s just selling hope with a calculator.

Also, I’m not taking a pill for 10 years because some ad says ‘50% reduction’ - not unless they pay me to.

Shayne Smith

OMG YES. I took a statin for a year and my legs felt like lead. Asked my doc for the numbers - turns out my risk dropped from 8% to 7.2%. I was like… so I’m paying $200 a month and feeling like a zombie for a 0.8% bump? No thanks. I started walking 30 mins a day instead. My cholesterol’s fine now. And my legs don’t hate me.

Doctors need to stop treating us like idiots with percentages.

Max Manoles

The cognitive dissonance in pharmaceutical marketing is staggering. Relative risk reduction is mathematically valid, but ethically indefensible when presented without absolute context. The FDA’s recent guidance is a step forward, but enforcement remains toothless. A 50% relative reduction from a 0.01% baseline is a 0.005% absolute change - statistically significant, clinically meaningless. Patients are not statistical units. They are human beings who deserve transparent, interpretable data - not marketing theater dressed as medical advice.

This isn’t just about pills. It’s about trust in institutions. And right now, that trust is being systematically eroded by corporate incentives disguised as science.

Annie Gardiner

But what if the real risk is that the drug is making you sick so they can sell you another drug for the side effects? I mean, think about it - if they tell you the absolute risk is low, but they don’t tell you the drug causes liver damage in 1 in 10,000, and then they sell you a liver pill… who’s really making money here?

It’s not medicine. It’s a pyramid scheme with prescriptions.

Rashmi Gupta

People in the US think they can buy health with pills. In India, we know better - if you can’t afford food, you can’t afford your medicine. Absolute risk? What’s the point if you can’t even get to the pharmacy? We don’t need fancy charts. We need clean water, vaccines, and doctors who show up.

Stop talking numbers. Start fixing systems.

Andrew Frazier

Y’all are overthinking this. It’s just a pill. If you’re too dumb to understand percentages, don’t take it. I got my blood pressure meds, I don’t care if it’s 2% or 50% - I feel better. And if you’re sitting there reading a 10-page post about stats instead of going for a walk, maybe your problem isn’t the drug - it’s your laziness.

Also, the FDA? They’re owned by Big Pharma. Just sayin’.

Mayur Panchamia

ABSOLUTE RISK? RELATIVE RISK? WHO CARES?! I’m from India - we don’t have time for this! My uncle took a blood pressure pill and died. The company said ‘only 0.0003% chance of death’ - guess what? It was HIS 0.0003%! So now I don’t trust ANY number that comes from a lab coat.

They sell you hope. Then they sell you grief. Then they sell you a funeral plan. It’s a TRIPLE-SCAM.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘NNT’ - if 99 people suffer for 1 person to live, that’s not science - that’s human sacrifice!

brenda olvera

I love how we talk about numbers like they’re the whole story - but health isn’t math. It’s your grandma’s cooking. It’s your sleep. It’s your stress. It’s whether you can afford the copay. I took my statin for 6 months. I felt like a zombie. I stopped. I started eating more veggies. My numbers improved. My soul improved too.

Don’t let a percentage tell you what your body already knows.

olive ashley

They’ve been lying to us since the 1950s. The tobacco industry did it. The opioid crisis did it. Now it’s statins and antidepressants. The same playbook: inflate the benefit, bury the risk, and make you feel guilty for not taking it.

Did you know the FDA’s advisory board has 70% financial ties to pharma companies? That’s not oversight - that’s a revolving door. And the ‘NNT’? That’s just a euphemism for ‘how many of you are we willing to sacrifice?’

You think you’re choosing health. You’re choosing a corporate KPI.

Chris Park

Let me ask you this - if your neighbor’s dog has a 0.01% chance of dying from eating a chocolate chip, and you give it a pill that reduces it to 0.0001%, are you a hero? Or are you just wasting money on a dog that’s fine? Now imagine that dog is you. And the chocolate chip is… life.

They’re selling you a cure for a problem you don’t have. And they’re making you feel broken for not taking it.

Wake up. This isn’t medicine. It’s psychological manipulation dressed in white coats.

Nigel ntini

This is exactly the kind of clarity we need more of. So many people are scared into taking meds they don’t need - or scared away from ones they do. The key is balance. Absolute risk tells you what’s real. Relative risk tells you what’s possible. But your values? Your lifestyle? Your fears? Those matter too.

Don’t let a percentage make your decision for you. Talk to your doctor. Ask for the numbers. But also ask: ‘Will this help me live better?’ Not just live longer.

And if your doctor rolls their eyes? Find a new one. You deserve better.

Ashish Vazirani

Look - I’m not saying the math is wrong - but the system is rigged. They don’t want you to understand absolute risk. They want you to feel FOMO. ‘What if you’re the one in 100 who gets the heart attack?’ - that’s the fear they sell. Meanwhile, the real risk is you’ll spend 10 years on pills, feel tired, and still die at 78 anyway.

And don’t get me started on the ‘NNT’ - if 100 people take it and only 1 benefits, who’s paying for the other 99’s side effects? YOU. Through insurance. Through taxes. Through your stress.

This isn’t science. It’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

Myles White

Let me just say - I spent 18 months reading every clinical trial on statins after my doctor pushed me to start one. I looked at the FDA’s public database, the Cochrane reviews, the JAMA meta-analyses. The absolute risk reduction for primary prevention in low-risk men? 0.6% over 5 years. The risk of developing diabetes? 0.3%. The risk of muscle damage? 0.5%. So statistically, you’re more likely to get diabetes or muscle pain than to avoid a heart attack - unless you’re already high-risk.

And yet, 80% of the patients I’ve talked to were told it was a ‘life-saving’ drug. No one mentioned the numbers. No one showed them the grid of 100 people with colored dots. No one said, ‘Here’s what this actually means for you.’

It’s not ignorance. It’s negligence. And it’s dangerous.

Doctors need training in risk communication. Not just in pharmacology. Because if you can’t explain it in plain terms, you shouldn’t be prescribing it.