When a pharmacist hands you a pill bottle with a different name than what your doctor wrote, you might wonder: is this really the same thing? It’s not just a label swap. Behind every generic drug substitution is a strict, science-backed verification process that pharmacists follow every day to make sure you get the same therapeutic effect - safely and reliably.

The Legal and Scientific Foundation

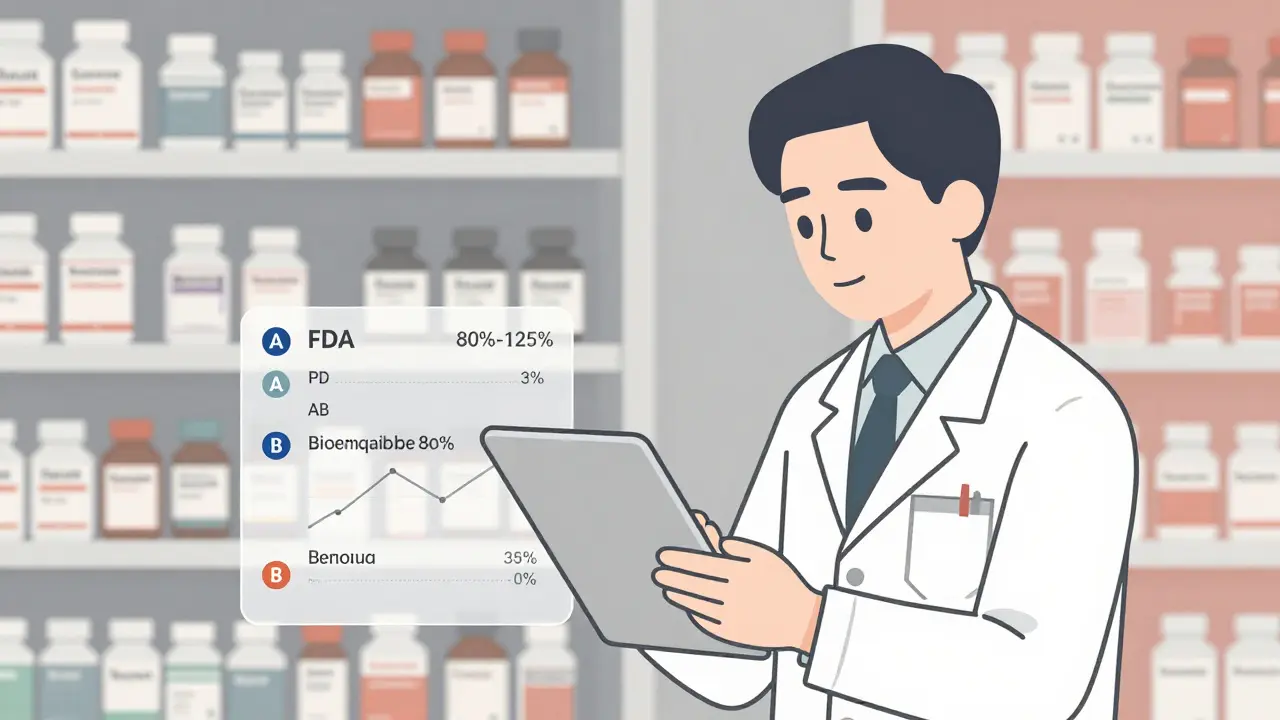

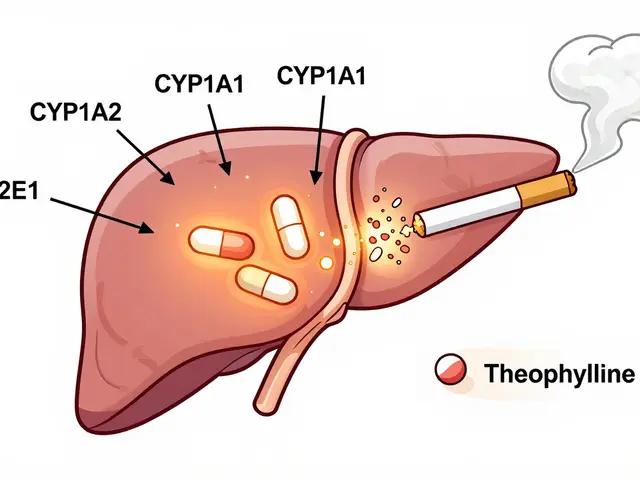

The system pharmacists use today didn’t happen by accident. It was built in 1984 with the Hatch-Waxman Act, which let the FDA approve generic drugs without repeating expensive clinical trials. Instead, manufacturers had to prove their version worked just like the brand-name drug. That proof? It’s called bioequivalence. Bioequivalence means the generic drug enters your bloodstream at the same rate and amount as the original. The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval for two key measurements - how fast the drug peaks in your blood (Cmax) and how much of it gets absorbed overall (AUC) - must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug. That’s not a guess. It’s a statistically proven window that ensures no meaningful difference in how the drug works in your body. For most drugs, that’s enough. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin - the FDA tightens the rules. In those cases, the acceptable range shrinks to 90-111%. Why? Because even a small change can cause serious side effects or make the drug ineffective.The Orange Book: The Pharmacist’s Bible

The tool every pharmacist relies on is the FDA’s Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations - better known as the Orange Book. It’s updated monthly and lists over 16,500 drug products as of April 2024. Each entry has a two-letter code that tells pharmacists whether substitution is allowed. The first letter is the most important:- A = Therapeutically equivalent. Safe to substitute.

- B = Not equivalent. Do not substitute.

How Pharmacists Verify Equivalence Step by Step

It’s not just opening the Orange Book and clicking “yes.” Pharmacists follow a clear, four-step protocol every time they consider a substitution:- Identify the reference listed drug (RLD) - This is the original brand-name drug the generic is copying. The Orange Book lists this clearly.

- Match active ingredient, strength, and dosage form - A 500mg tablet of amoxicillin must match exactly. No exceptions. Even a different shape or color doesn’t matter - only the science does.

- Check the TE rating - Must be “A” or “AB.” If it’s “B,” substitution is legally prohibited.

- Confirm no “Do Not Substitute” instruction - The prescriber may have written “Dispense as Written” on the prescription. That overrides everything.

What Happens When the Drug Isn’t Listed?

About 5.7% of generic substitutions involve drugs not yet in the Orange Book. This happens with newer generics or complex formulations like inhalers, topical creams, or compounded products. In those cases, pharmacists can’t rely on the Orange Book’s code. Instead, they turn to professional judgment. The FDA provides guidance for these situations. Pharmacists review published bioequivalence studies, compare manufacturing processes, and consult trusted databases like Micromedex or Lexicomp. But here’s the catch: those are secondary tools. Only the Orange Book has legal standing. If a pharmacist substitutes a non-Orange Book-listed drug and something goes wrong, they could face disciplinary action - as happened in the 2019 Texas case State Board of Pharmacy v. Smith, where a pharmacist was sanctioned for substituting a product not rated in the Orange Book.Why Other Databases Aren’t Enough

You might think, “Why not just use Micromedex or First Databank?” They’re useful. But they’re not the law. A 2021 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found that 99.3% of pharmacists use the Orange Book as their primary source. Only 62.7% use commercial databases - and even then, mostly as backups. Why? Because the Orange Book is the only source that’s federally mandated and legally defensible. State laws in 49 states (all except Massachusetts) require pharmacists to use it as the basis for substitution decisions. Texas Administrative Code §309.3(a) says it outright: “Pharmacists shall use… the Orange Book.”

Training and Accuracy

Pharmacists don’t learn this on the fly. Every new hire gets formal training - typically 2 to 4 hours - on how to read the Orange Book, interpret TE codes, and handle edge cases. The National Community Pharmacists Association reports that 92.4% of pharmacies include this in onboarding. After training, competency assessments show 89.3% accuracy in equivalence verification. That’s high - but not perfect. That’s why many pharmacies use double-check systems, especially for high-risk drugs. A second pharmacist reviews the substitution before the prescription leaves the counter.Challenges Ahead: Complex Drugs and Biosimilars

The system works brilliantly for pills and capsules. But it’s under pressure from complex products. Inhalers, topical corticosteroids, and injectables don’t always behave the same way in the body just because their chemical makeup matches. Traditional bioequivalence metrics - based on blood levels - don’t capture everything. The FDA is responding. As of Q2 2024, it has issued product-specific guidances for 1,850 complex drugs. These outline new testing methods - like in vitro dissolution profiles or clinical endpoint studies - to prove equivalence where pharmacokinetics fall short. Then there’s the rise of biosimilars. These aren’t generics. They’re highly similar versions of biologic drugs - complex proteins made from living cells. The FDA tracks them in the Purple Book, not the Orange Book. As of June 2024, only 47 of 350 approved biosimilars were listed there. That creates confusion. Pharmacists don’t have the same clear “A” rating system to guide them. The FDA’s 2023 Strategic Plan for Generic Drugs now lists “enhancing therapeutic equivalence evaluation for complex products” as a top priority - with $28.5 million allocated through GDUFA III to fund new research.The Bigger Picture: Why It Matters

In 2023, 90.7% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. were for generic drugs. That’s 8.9 billion prescriptions. Without accurate equivalence verification, that system collapses. Patients would lose trust. Costs would spike. And lives could be at risk. The current system saves the U.S. healthcare system $12.7 billion annually. It’s not just about money. It’s about access. Generics make life-saving medications affordable for millions. But that access only works if the substitution is safe. The science is solid. The process is standardized. The legal framework is clear. And pharmacists - trained, vigilant, and accountable - are the ones making sure it all holds together.Can a pharmacist substitute a generic drug without the doctor’s permission?

Yes - but only if the drug is rated ‘A’ or ‘AB’ in the FDA Orange Book and the prescriber hasn’t written ‘Dispense as Written’ on the prescription. State laws allow substitution by default, but the pharmacist must verify both the therapeutic equivalence rating and the prescriber’s instructions before making the switch.

Are all generic drugs in the Orange Book?

No. About 5.7% of generic drugs are not yet listed, especially newer products or complex formulations like inhalers and topical creams. Pharmacists must use professional judgment and consult additional resources like bioequivalence studies or FDA guidance in these cases - but they cannot rely on the Orange Book for legal protection.

What does an ‘AB’ rating mean in the Orange Book?

An ‘AB’ rating means the generic drug is both pharmaceutically equivalent (same active ingredient, strength, dosage form) and bioequivalent (proven through human studies to have the same absorption rate and amount in the bloodstream) as the brand-name reference drug. This is the standard rating for most generic pills and capsules and is the only one that allows automatic substitution under state laws.

Why do some pharmacists hesitate to substitute generics for narrow therapeutic index drugs?

Even though the FDA allows substitution for most narrow therapeutic index drugs if they’re AB-rated, some pharmacists and prescribers prefer to avoid switching due to the small margin of safety. For drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine, even minor differences in absorption can affect blood levels. While studies show no significant increase in adverse events, the cautious approach remains common - especially when patients are stable on a brand.

Is the Orange Book the only legal source for equivalence verification?

Yes. In all 50 U.S. states and territories, the FDA Orange Book is the legally required reference for therapeutic equivalence. While commercial databases like Micromedex or Lexicomp are useful for additional context, they do not carry legal weight. Pharmacists who substitute based on non-Orange Book sources risk disciplinary action or malpractice claims.

How are biosimilars handled differently from generic drugs?

Biosimilars are not considered generic drugs because they’re made from living cells, not synthesized chemicals. They’re tracked in the FDA’s Purple Book, not the Orange Book. Unlike generics, there’s no standardized ‘A’ rating system for biosimilars yet. Pharmacists must rely on prescriber instructions and product labeling, as interchangeability is still being defined for most products.

Sam Davies

So let me get this straight - we’re trusting a 40-year-old law to decide if my blood thinner won’t kill me? Cool. Cool cool cool.

Vincent Clarizio

You know what’s wild? The entire system is built on a statistical window of 80–125% bioequivalence - which, if you think about it, is basically saying, 'Hey, as long as it’s not totally off, we’re good.' But then for warfarin? Suddenly we’re micromanaging to 90–111%. That’s not science - that’s panic dressed up as regulation. We treat drugs like they’re GPS coordinates when they’re more like mood rings. The body doesn’t care about FDA margins. It cares about how you slept last night, whether you drank coffee, if your liver’s having a bad day. We’ve turned pharmacology into a spreadsheet game, and patients are just data points with insurance cards.

Jennifer Littler

The Orange Book is the gospel, but the real liturgy happens in the pharmacy back room where the techs cross-check the TE codes while the pharmacist stares at the screen like it’s a Rorschach test. I’ve seen it. It’s not automation. It’s ritual.

Madhav Malhotra

In India, we don’t even have an Orange Book. We have pharmacies that look up generics on WhatsApp groups. And yet, people live. Maybe the system works because it’s simple, not because it’s perfect.

Priya Patel

I used to panic every time my pill looked different. Now I just trust the pharmacist. 🙏❤️

Matthew Miller

98.7% AB-rated? That’s a lie. You’re ignoring the 1.3% that kill people. The FDA’s meta-analysis? Funded by generic manufacturers. Conflict of interest much? You think this is safe? You’re the reason people die quietly in their homes because no one checked the bioequivalence study from 2012 that got buried under 47 revisions.

Jason Shriner

so like... the orange book is basically the bible but with more tables and less miracles? lol

Roshan Joy

I work in a pharmacy in Delhi, and we don’t have the Orange Book - but we do have patient history, doctor calls, and a lot of gut instinct. Sometimes, the best verification isn’t in a database - it’s in the conversation you have with someone who’s been taking this drug for 10 years. 🌿

Michael Patterson

The Orange Book is fine I guess but have you seen how many typos are in the PDFs? Like, 'AB' becomes '4B' sometimes. And no one checks. I swear if I get a drug that's 4B rated I'm suing the FDA.

Alfred Schmidt

I’ve been on levothyroxine for 12 years. Switched generics three times. My TSH went from 2.1 to 8.9 in 6 weeks. No one listened. Then I found out the generic was AB-rated. AB-rated?! What does that even mean if my body is falling apart?! The system is broken. It’s not about statistics - it’s about MY thyroid. And you? You’re just reading a manual.

Sean Feng

This post is too long nobody cares

Adewumi Gbotemi

In Nigeria, we don’t have this system. But we have people who travel 100km to get the same brand because they know what works. Maybe the answer isn’t more rules - it’s more access to what works.

Priscilla Kraft

I love that pharmacists are the unsung heroes here. 🤍 They’re the ones holding the line between corporate cost-cutting and patient safety. Seriously, next time you get your prescription, say thank you. It’s not just a label swap - it’s a quiet act of care.

Alex Smith

You know what’s ironic? The whole system exists because brand-name companies wanted to protect their profits. Hatch-Waxman was a compromise - let generics in, but make them jump through hoops so they don’t undercut too hard. Now we treat bioequivalence like it’s divine law, but the truth is, it was written by lawyers and lobbyists. The science? It’s just the cover story. And yet - somehow - it still works. That’s the real miracle.