When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, the race to bring out a cheaper generic version begins - not with a factory, but in a courtroom. This is where Paragraph IV certification comes in. It’s the legal tool that lets generic drug makers challenge patents before they expire, and it’s one of the biggest reasons why Americans pay less for prescriptions today than they did 30 years ago.

What Exactly Is Paragraph IV?

Paragraph IV isn’t a law. It’s a clause in the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, a piece of legislation designed to balance two competing goals: rewarding innovation by drug companies and making medicines affordable by letting generics enter the market faster. Under this system, when a generic company wants to sell a copy of a brand-name drug, it files what’s called an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA. Part of that application includes a certification about the patents listed for the brand drug in the FDA’s Orange Book. There are four types of certifications. Paragraph I says the patent has expired. Paragraph II says it will expire soon. Paragraph III says the generic will wait until the patent runs out. But Paragraph IV? That’s the one that changes everything. It says: “This patent is invalid, unenforceable, or we’re not breaking it.” That’s not just a bold claim - it’s a legal trigger. By filing a Paragraph IV certification, the generic company commits what’s called an “artificial act of infringement.” That sounds odd, but it’s intentional. It lets the brand company sue right away, even though the generic hasn’t sold a single pill yet. This setup forces a showdown in federal court before the generic can even launch.The 45-Day Clock and the 30-Month Stay

Once the brand company gets the Paragraph IV notice, they have exactly 45 calendar days to file a patent infringement lawsuit. If they don’t, the generic can move forward without delay. But if they do - and they almost always do - a 30-month regulatory stay kicks in. That means the FDA can’t approve the generic drug for 30 months, no matter how strong the case is. This stay doesn’t start when the generic files. It starts when the brand company receives the notice. That timing matters. Some generics wait until the last possible moment to file, hoping to catch the brand off guard. Others file early to lock in first-to-file status. The clock runs regardless of whether the case is going well or poorly. And even if the court rules in favor of the generic before 30 months are up, the FDA still has to wait until the stay expires - unless the patent is invalidated outright.How Do Generic Companies Win?

Winning a Paragraph IV case isn’t about having the biggest legal team. It’s about finding the patent’s weak spot. Most successful challenges focus on one of two things: invalidity or non-infringement. Invalidity means the patent shouldn’t have been granted in the first place. Maybe the drug’s formula was already described in an old scientific paper (prior art). Maybe it’s just an obvious tweak to something that already existed (obviousness). Teva’s challenge to Pfizer’s Lyrica® patent in 2019 succeeded because the court agreed the patent covered a method of use that was already known - not a new invention. Non-infringement is trickier. It means the generic drug is different enough from the patented version that it doesn’t violate the patent claims. This is where claim construction - the court’s interpretation of the patent’s exact wording - becomes everything. A single word like “solution” vs. “suspension” can decide whether a generic can launch or not. In one 2017 case, Mylan lost a $1.1 billion lawsuit because the court decided their version used a chemical process covered by Novartis’ patent.

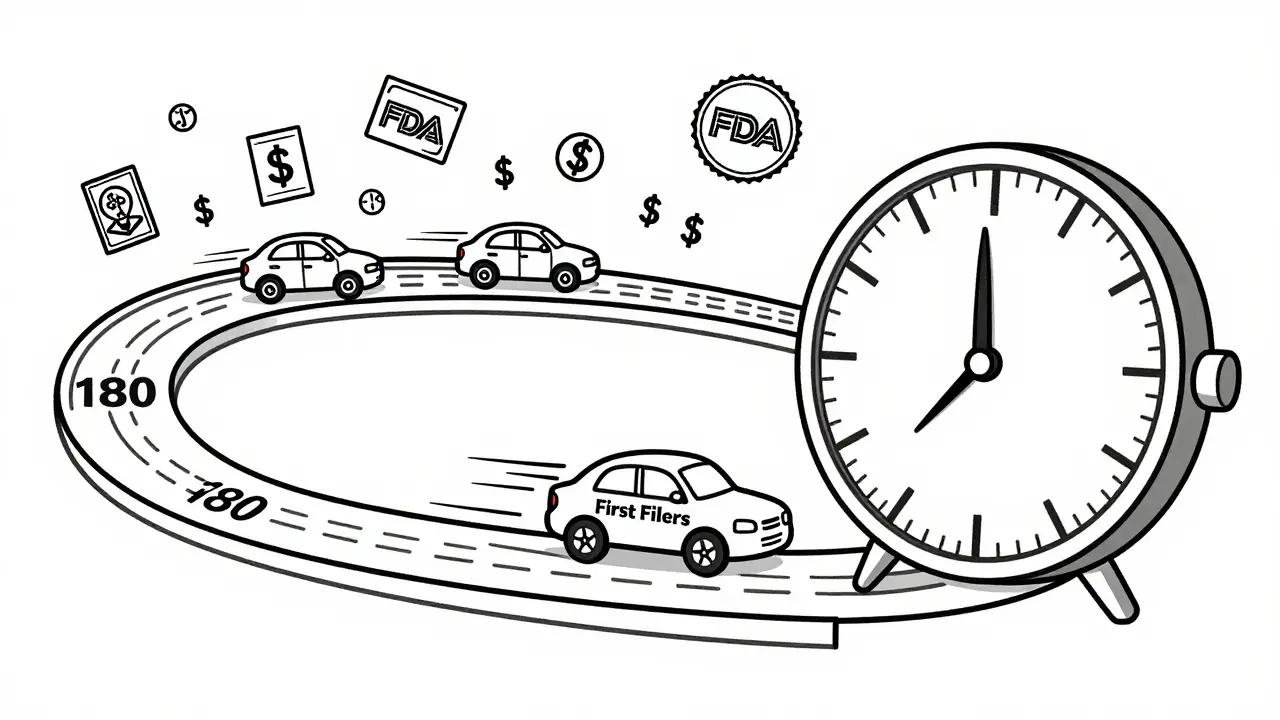

The 180-Day Exclusivity Prize

Here’s the real incentive: the first generic company to file a successful Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of exclusive market access. No other generics can enter during that time. That’s not just a head start - it’s a goldmine. During those 180 days, the first filer typically captures 70-80% of the generic market. In 2021, Barr Labs’ challenge to Eli Lilly’s Prozac® patent led to a court ruling that invalidated a key patent. Barr launched immediately and made hundreds of millions in revenue before other generics entered. That’s why so many generic companies race to be first. In fact, 87% of Paragraph IV filers aim for that first-to-file spot, according to a 2014 FTC report. But there’s a catch. If the first filer doesn’t actually launch within 75 days of winning, or if they get sued by another generic over patent disputes, they can lose their exclusivity. That’s why timing, manufacturing readiness, and legal strategy have to line up perfectly.Why This System Is Under Pressure

The original idea behind Paragraph IV was simple: challenge bad patents, get generics in fast, save money. But over time, brand companies got smarter. Instead of one patent per drug, they now file an average of 4.8 - many covering minor changes like pill coatings, dosing schedules, or how the drug is taken. These are called “secondary patents.” They don’t protect the active ingredient. They protect the packaging, the timing, or the way it’s used. And they’re harder to knock down. AbbVie’s Humira® had over 100 patents listed in the Orange Book. Generic companies tried and failed to challenge most of them. The result? Humira stayed exclusive for nearly 20 years - far beyond its original 20-year patent term. This practice, called “patent thickets,” has pushed the average effective market exclusivity for new drugs from 12.1 years in 1995 to 14.7 years in 2022, according to the Congressional Budget Office. That’s not innovation - it’s delay. And then there’s the cost. The average Paragraph IV lawsuit costs $7.8 million. That’s more than three times the cost of a patent challenge at the USPTO. Most small generic companies can’t afford it. That’s why only about 20 companies handle 80% of all Paragraph IV filings.

Settlements, Pay-for-Delay, and New Rules

Most Paragraph IV cases - 76% - never go to trial. They settle. And too often, those settlements look suspicious. The brand company pays the generic to delay entry. That’s called “pay-for-delay.” In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Actavis that these deals could violate antitrust laws. But they still happen. In 2022, the FDA cracked down on brand companies using citizen petitions to block generic approvals. These petitions, often filed just before a patent expires, claim safety concerns that turn out to be baseless. The FTC found they were used in 32% of Paragraph IV cases. The 2023 CREATES Act helps generics get the samples they need to test bioequivalence - something brand companies used to withhold. And the Inflation Reduction Act lets Medicare negotiate drug prices, which changes the financial math for brand companies. If they know the government will cap prices anyway, they might be less willing to fight to extend exclusivity.What Happens When It Works?

When Paragraph IV works the way it was meant to, the results are dramatic. After a successful challenge, generic prices drop an average of 79% within six months, according to research from HEC Paris. Between 2009 and 2019, Paragraph IV-driven generic entries saved U.S. consumers $1.68 trillion. In 2021 alone, 287 brand-name drugs lost exclusivity thanks to Paragraph IV filings. That’s $98.3 billion in potential generic sales. Without this system, those drugs would still be priced at brand levels - often thousands of dollars per month. The European Union doesn’t have a Paragraph IV equivalent. Generic entry there takes longer, and prices stay higher. The U.S. system isn’t perfect, but it’s the most effective tool in the world for accelerating generic access.What’s Next?

The FTC is now pushing to reform Paragraph IV to stop patent thickets and evergreening. Congress is considering limits on how many patents can be listed in the Orange Book. Some experts want to merge Paragraph IV litigation with USPTO post-grant reviews to reduce costs. But for now, the system still works - if you know how to use it. Generic companies that invest in deep patent analysis, build strong legal teams, and prepare manufacturing lines in advance are the ones that win. The brand companies that rely on endless patents and legal delays are the ones losing ground. The next time you fill a prescription and pay $10 instead of $500, thank Paragraph IV. It’s not glamorous. It’s not simple. But it’s the reason millions of people can afford their medicine.What is the purpose of Paragraph IV certification?

Paragraph IV certification allows a generic drug manufacturer to challenge the validity, enforceability, or non-infringement of a patent listed for a brand-name drug in the FDA’s Orange Book. This triggers a legal process that can lead to earlier generic market entry, balancing patent protection with public access to affordable medications.

How does Paragraph IV trigger a 30-month stay?

When a brand-name company files a patent infringement lawsuit within 45 days of receiving a Paragraph IV notice, the Hatch-Waxman Act automatically imposes a 30-month stay on FDA approval of the generic drug. The stay begins when the lawsuit is filed, not when the notice is sent, and it prevents the FDA from approving the generic until either the patent expires, the court rules in favor of the generic, or the 30 months pass.

Why is the first-to-file generic company rewarded with 180 days of exclusivity?

The 180-day exclusivity period is designed to incentivize generic companies to take the legal and financial risk of challenging patents. The first company to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification and successfully defend the challenge gets a head start on the market, allowing them to capture the majority of generic sales before competitors enter - making the expensive litigation financially worthwhile.

What’s the difference between Paragraph IV and IPR (Inter Partes Review)?

Paragraph IV challenges happen in federal district court and require a lower burden of proof (preponderance of evidence) to invalidate a patent. IPRs occur at the USPTO and require clear and convincing evidence. Paragraph IV is more expensive ($7.8M average) but has a higher success rate (65%) than IPRs (35%). IPRs are faster and cheaper but don’t trigger FDA approval delays or exclusivity rewards.

Why do brand companies list so many patents in the Orange Book?

Brand companies list multiple patents - including secondary ones covering formulations, dosing methods, or uses - to create “patent thickets.” This strategy delays generic entry by forcing challengers to fight multiple legal battles. Between 1995-2000, 38% of new drugs had three or more Orange Book patents. By 2015-2020, that number jumped to 72%.

Can a generic company lose money even if they win a Paragraph IV case?

Yes. Even if a generic wins the patent case, they may have spent millions in legal fees and manufacturing prep. If they don’t launch within 75 days of winning, they can lose their 180-day exclusivity. In some cases, like Mylan’s challenge to Gleevec®, the generic company was found guilty of willful infringement and ordered to pay over $1 billion in damages - even if the patent was later invalidated.

sam abas

Look, i’ve read this thing twice and i still don’t get why we’re acting like paragraph iv is some kind of miracle cure. sure, it saved us a trillion bucks, but at what cost? every time a generic company files one of these, it’s a full-blown lawsuit circus that takes years and drains resources from actual R&D. and don’t even get me started on how the first filer gets 180 days of monopoly - that’s just legal cartels with better lawyers. the system was meant to be a balance, but now it’s just a game of who can afford the shiniest briefs. and yeah, i know i’m not the first to say this, but nobody listens until it’s their insulin bill that’s $800.

Clay .Haeber

Oh wow, another love letter to the FDA’s legal tango. Let me grab my monocle and monocle holder - because clearly, we’re here to celebrate how patent thickets are just ‘strategic innovation’ and not corporate extortion dressed up in legalese.

And let’s not forget the 76% settlement rate - which, surprise, is 76% pay-for-delay deals with a side of ‘we’ll let you sell generics… after we pay you not to.’ Genius. Absolute genius. If this were a Netflix doc, it’d be called ‘The Billion-Dollar Game of Chicken.’

Priyanka Kumari

This is such an important topic, and I really appreciate how clearly the post breaks it down. As someone from India where access to affordable medicines is still a daily struggle, seeing how the U.S. system works - even with its flaws - gives me hope that similar frameworks can be adapted elsewhere.

The 180-day exclusivity incentive is smart, but I agree with others that the patent thickets are abusive. Maybe a cap on Orange Book listings, or mandatory public disclosure of all patent claims upfront, could help? We need more transparency, not more legal loopholes. Thank you for highlighting the human impact - real people are saving thousands because of this.

Avneet Singh

Let’s be real - paragraph IV is just a regulatory arbitrage mechanism masquerading as consumer advocacy. The entire framework is a relic of 1980s legislative compromise, and the fact that we still treat it as a gold standard is a testament to how little the FDA has evolved.

And don’t even mention the 30-month stay - that’s not a stay, it’s a statutory delay mechanism engineered by pharma lobbyists. The ‘artificial act of infringement’ is a legal fiction so convoluted it belongs in a law school exam, not public policy. The real innovation isn’t in generics - it’s in how Big Pharma weaponizes the system.

Kimberly Mitchell

It’s not about saving money. It’s about accountability. When a company spends billions developing a drug, they deserve protection. But when they file 100 patents on the color of the pill? That’s not innovation. That’s greed. And the fact that we reward the first generic filer with 180 days of monopoly? That’s just swapping one monopoly for another. Where’s the ethics in that? This system doesn’t serve patients - it serves lawyers and hedge funds.

Randall Little

Fun fact: the EU doesn’t have paragraph IV. And guess what? Their generic prices are higher, and access is slower. But they don’t have 20-year patent extensions on Humira either.

So yeah, the U.S. system is messy, expensive, and full of loopholes - but it’s the only one that actually forces a showdown before market entry. In Europe, generics just wait. Here, they fight. And sometimes, they win. That’s not chaos - that’s competition. Maybe we need to fix the abuse, not scrap the whole thing.

Lethabo Phalafala

I remember when my mom had to choose between her diabetes meds and groceries. She took the generics - the ones that came out because someone dared to challenge a patent. That’s not legal jargon - that’s survival.

And now you want to talk about ‘patent thickets’ and ‘settlements’? Fine. But when your child needs insulin and the price is still $300 a vial? That’s not a policy debate. That’s a moral failure. Paragraph IV isn’t perfect - but it’s the only thing standing between people and bankruptcy. Don’t take it away. Fix it. But don’t you dare pretend it’s the problem.

Lance Nickie

paragraph iv = generic mafia with a law degree.

Milla Masliy

I live in a small town in Ohio. My neighbor’s son has cystic fibrosis. His meds used to cost $12,000 a month. Now? $180. Because of Paragraph IV.

I don’t care if the system’s messy. I don’t care if Big Pharma is gaming it. I care that a kid can breathe. That’s what matters.

So yeah, maybe we need reform. But let’s not throw out the baby with the bathwater. The fact that this system works at all - that it saves billions and lives - is a miracle in a broken system. Let’s fix the loopholes, not the heart.