When people talk about COPD, they often treat it like one disease. But that’s like calling a car and a truck both "vehicles" and expecting them to fix the same way. Chronic bronchitis and emphysema are the two main pieces of COPD - and they’re not just different in symptoms. They’re different in what’s happening inside your lungs, how they’re diagnosed, and how they respond to treatment. If you or someone you care about has COPD, understanding this split isn’t just academic. It can change everything - from how often you end up in the hospital to whether your breathing gets better at all.

What’s Actually Damaged in Each Condition?

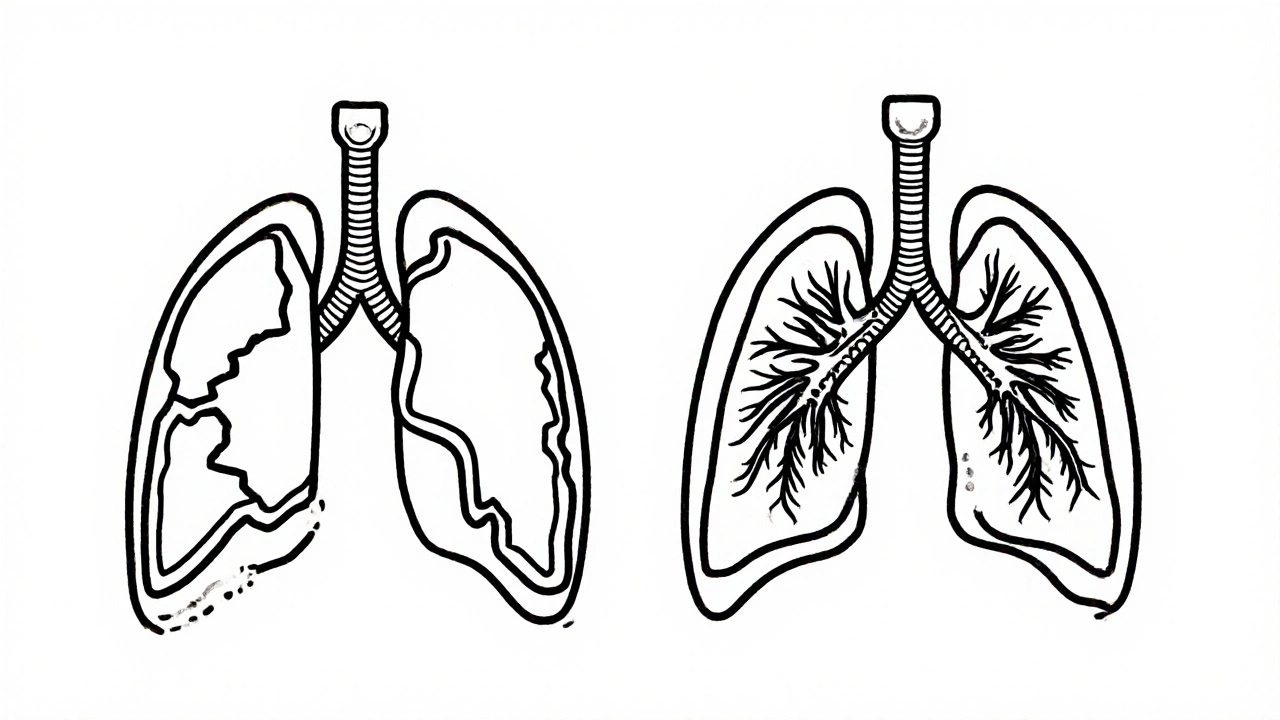

Emphysema attacks the tiny air sacs in your lungs, called alveoli. These are the places where oxygen moves into your blood and carbon dioxide leaves. In emphysema, the walls between these sacs break down. They don’t just get inflamed - they’re destroyed. This creates big, useless air spaces where gas exchange should happen. The result? Your lungs lose their natural spring. They can’t push air out properly. That’s why people with emphysema feel like they’re always gasping for air, even when they’re sitting still. By the time it’s advanced, up to 50% of the lung’s elastic recoil is gone. Pulmonary tests show a sharp drop in DLCO - the measure of how well oxygen crosses into your blood - often below 60% of what’s normal.

Chronic bronchitis, on the other hand, is all about the airways. The bronchial tubes become swollen and lined with too much mucus. The cells that normally sweep mucus out - called cilia - get damaged. Goblet cells, which make mucus, multiply by 300% to 500%. Instead of producing 10-100 mL of mucus a day like a healthy lung, a chronic bronchitis lung can make 100-200 mL. That’s a cup or more of thick gunk daily. You’re not just coughing - you’re fighting to clear your airways. That’s why the clinical definition requires a productive cough for at least three months a year, for two years straight.

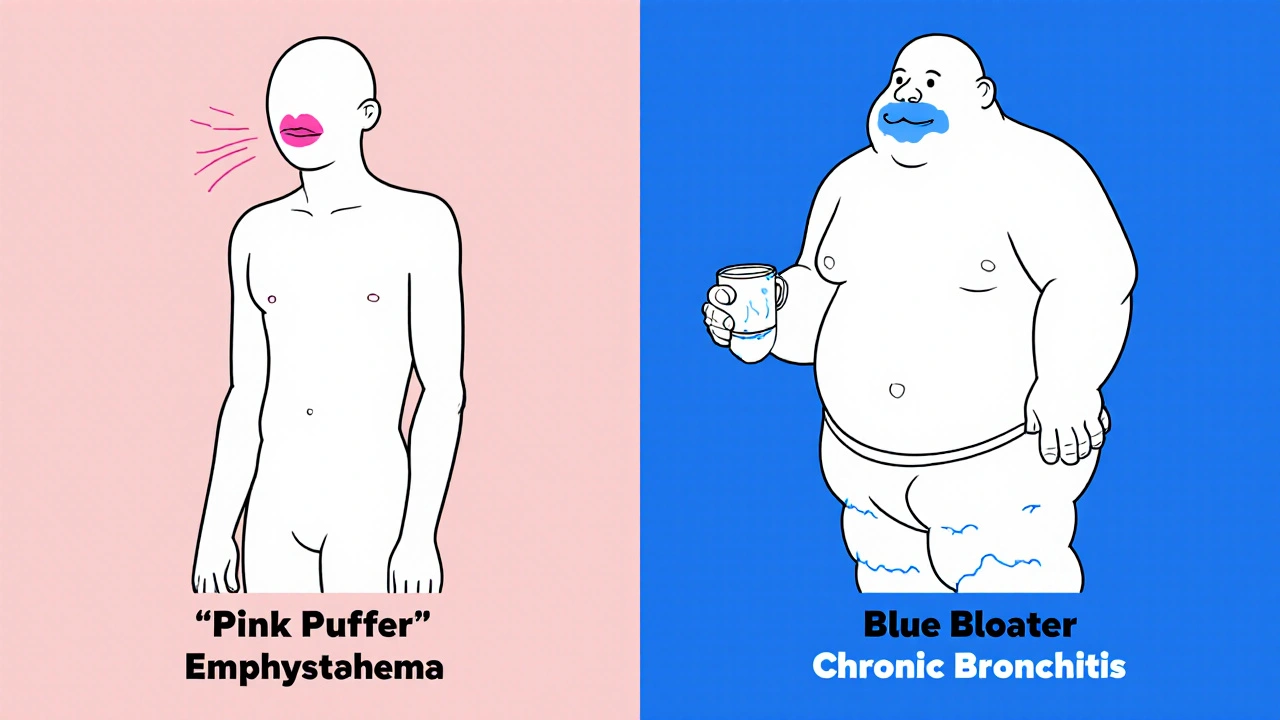

The Classic Signs: Pink Puffer vs. Blue Bloater

You’ll hear doctors use old terms like "pink puffer" and "blue bloater." They’re not fancy medical jargon - they’re shorthand for how these two conditions show up in real people.

The "pink puffer" has emphysema. They’re often thin, breathe fast - 25 to 30 breaths per minute - and look like they’re always trying to catch air. Their lips and fingernails stay pink because they’re hyperventilating to keep oxygen levels up, usually around 92-95%. But their chest looks barrel-shaped because their lungs are overinflated. They can’t speak in full sentences - five words at a time is common. Their biggest problem isn’t mucus. It’s air hunger.

The "blue bloater" has chronic bronchitis. Their skin may look slightly blue, especially around the lips and fingertips, because their blood oxygen is low - often 85-89%. They’re more likely to have swollen ankles from fluid buildup (cor pulmonale) because their heart is working overtime to pump blood through damaged lungs. They cough all day, sometimes clearing 100 mL of mucus in the morning alone. They’re not always short of breath at rest, but they tire quickly walking even short distances. Their cough is the problem - and it gets worse in winter.

How Doctors Tell Them Apart

There’s no single test that says "this is emphysema" or "this is bronchitis." But pulmonologists use a mix of tools to see which one dominates.

- DLCO test: If your diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide is below 60% of predicted, emphysema is likely. This test measures how well oxygen moves from your lungs into your blood - and it drops hard in emphysema.

- CT scan: High-resolution scans show emphysema as dark, low-density patches covering more than 15% of lung volume. For chronic bronchitis, the airway walls appear thickened - over 60% wall area on expiratory scans.

- 6-minute walk test: Emphysema patients usually drop their oxygen saturation below 88% within two minutes. Chronic bronchitis patients stay saturated but stop walking because they’re too out of breath.

- FEV1/FVC ratio: Both conditions show this ratio below 70%, which confirms airflow obstruction. But in chronic bronchitis, the obstruction is more about resistance in the airways. In emphysema, it’s about loss of recoil.

Doctors also look at your history. Did you smoke for 30 years and now can’t walk up a hill? Emphysema. Did you smoke and cough up mucus every winter for a decade? Chronic bronchitis. But here’s the catch: 85% of people with advanced COPD have features of both. Pure cases are rare.

Treatment Isn’t One-Size-Fits-All

One of the biggest mistakes in COPD care is treating everyone the same. A 2022 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that patients who got treatment matched to their phenotype had 27% fewer hospital visits.

For emphysema: The goal is to reduce lung volume so the remaining healthy tissue can work better. That’s why endobronchial valves - tiny devices placed in the airways to collapse damaged areas - help 65% of eligible patients improve their walking distance by 35%. Lung volume reduction surgery also works for some. Oxygen therapy is often needed, but portable concentrators can be bulky. New treatments like inhaled alpha-1 antitrypsin (for those with the genetic deficiency) can improve FEV1 by 20% in a year.

For chronic bronchitis: Mucus is the enemy. Mucolytics like carbocisteine reduce flare-ups by 22%. Hypertonic saline nebulizers thin the gunk - 73% of users report easier clearing. Roflumilast, a pill that reduces inflammation in the airways, cuts exacerbations by 17.3% in people who have two or more flare-ups a year. But here’s the warning: inhaled steroids, often used in asthma, increase pneumonia risk by 40% in chronic bronchitis patients. That’s why guidelines now recommend LAMA/LABA combos (long-acting bronchodilators) as first-line.

What Life Looks Like Day to Day

Real people don’t live by test results. They live with symptoms.

On COPD patient forums, emphysema users describe "air hunger" that makes conversation impossible. One wrote: "I can say ‘I need water’ - that’s it. Then I have to stop and breathe." They avoid stairs, crowds, even talking on the phone. But their sleep is often better - only 41% report nighttime coughing.

Chronic bronchitis patients? They’re tied to mucus clearance. One Reddit user measured his morning output in a measuring cup - 100 mL every day for eight years. He spends 20-30 minutes doing chest physiotherapy. Others use acoustic devices that vibrate mucus loose - new in Europe, showing a 32% drop in flare-ups. But the daily routine is brutal: four to six inhalers, multiple nebulizer treatments, and constant worry about winter colds turning into pneumonia.

Why This Matters for Your Future

COPD is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide. But it’s not inevitable. And it’s not hopeless.

If you have emphysema, quitting smoking won’t reverse the damage - but it will stop it from getting worse faster. Lung volume reduction procedures can give you back mobility. New therapies are coming: bronchoscopic thermal vapor ablation is showing 78% success in improving lung function at two years.

If you have chronic bronchitis, managing mucus is everything. Avoiding colds, using humidifiers, staying hydrated, and taking mucolytics regularly can keep you out of the ER. New drugs targeting TMEM16A channels - which control mucus production - are in trials and could be game-changers.

The future of COPD isn’t one drug for everyone. It’s precision medicine. The NIH’s 2024-2028 plan is investing in biomarkers - like blood eosinophil counts - to predict who will respond to which treatment. By 2026, we’ll know more about who benefits from biologics, who needs valves, and who needs mucus-thinning tech.

Right now, the biggest gap isn’t in science - it’s in recognition. Only 42% of primary care doctors routinely differentiate between these two types. If you’ve been told you have COPD and you’re not getting better, ask: "Which part do I have?" And then ask: "What’s the plan for that?"

What to Do Next

- If you’re diagnosed with COPD, ask for a DLCO test and a high-resolution CT scan. These aren’t always ordered - but they’re essential.

- Track your symptoms. Are you mostly coughing and clearing mucus? Or are you gasping for air with little cough? That tells your doctor which phenotype you’re leaning toward.

- Don’t accept the same inhaler regimen if you’re still struggling. Ask about roflumilast (for mucus) or endobronchial valves (for air trapping).

- Join a support group. The COPD Foundation has local chapters and online forums where people share real-life tips - like how to use a measuring cup to track mucus, or which portable oxygen device actually fits in a purse.

COPD isn’t a death sentence. But treating it like a single disease is. The science has moved on. It’s time your care did too.

Can you have both chronic bronchitis and emphysema at the same time?

Yes - and most people with moderate to severe COPD do. While chronic bronchitis and emphysema are defined as separate conditions, they often overlap. Studies show only about 15% of advanced COPD patients have pure forms. The rest have a mix: airway inflammation from bronchitis and alveolar destruction from emphysema. That’s why treatment needs to be tailored - not just based on one symptom, but on the full picture.

Is COPD the same as asthma?

No. Asthma is reversible airway narrowing, often triggered by allergens or exercise, and usually starts in childhood. COPD is progressive, caused mainly by smoking or long-term exposure to irritants, and typically shows up after age 40. In asthma, lung function improves with bronchodilators. In COPD, improvement is limited, and damage is permanent. While both cause wheezing and shortness of breath, their causes, progression, and long-term treatments are very different.

Does quitting smoking help if I already have COPD?

Yes - even if you’ve had COPD for years. Quitting won’t reverse damage already done, but it slows the decline in lung function by up to 50%. People who quit after diagnosis live longer, have fewer flare-ups, and respond better to treatments. The damage from smoking continues as long as you smoke. Stopping is the single most effective thing you can do to protect what’s left of your lungs.

Why do some COPD patients need oxygen and others don’t?

It depends on how much oxygen your lungs can deliver to your blood. Emphysema patients often need oxygen because their alveoli are destroyed and can’t transfer oxygen well. Chronic bronchitis patients may not need it unless they develop severe hypoxemia - low blood oxygen - often from repeated infections or heart strain. Doctors use pulse oximetry and arterial blood gas tests to decide. Oxygen is only prescribed if your levels stay below 88% at rest or during activity.

Are there new treatments for COPD on the horizon?

Yes. For emphysema, bronchoscopic thermal vapor ablation is showing 78% success in improving lung function at two years. For chronic bronchitis, new mucoregulators targeting TMEM16A channels are in late-stage trials and could reduce mucus production at the source. Inhaled alpha-1 antitrypsin for genetic emphysema was approved in 2023 and improves FEV1 by 20% in a year. There’s also growing use of acoustic mucus-clearing devices in Europe, which reduced exacerbations by 32% in recent trials. The focus is shifting from broad symptom control to targeted, phenotype-specific therapy.

Sean Hwang

Man, this post is straight fire. I’ve got a buddy with COPD and he never knew the difference between bronchitis and emphysema until I showed him this. Now he’s asking his doc for a DLCO test. Small wins, you know?

Kevin Wagner

THIS. RIGHT. HERE. We’ve been treating COPD like it’s one big lump of rotten meat when it’s actually two different beasts with different teeth and claws. If your doctor still hands you the same inhaler cocktail for everyone, they’re not treating you-they’re just throwing darts in the dark. Time to demand better. Your lungs didn’t sign up for this nonsense.

gent wood

I’ve spent years working with respiratory patients in the NHS, and this breakdown is spot-on. The pink puffer versus blue bloater distinction still holds up, even if some younger clinicians dismiss it as outdated. The real tragedy? Most primary care referrals never get the CT or DLCO. It’s not just about knowledge-it’s about systemic neglect. We need better protocols, not just better posts.

Dilip Patel

USA doctors always overcomplicate everything. In India we just give bronchodilators and tell them to stop smoking. Why need CT scan? Why need DLCO? Smoking bad, cough bad, breathe hard bad. Simple. You overthink, you overpay. We fix with cheap medicine and willpower. No fancy machines needed.

Jane Johnson

I find it concerning that this post assumes all patients have access to high-resolution CT scans and endobronchial valves. In rural America, many can’t even get a pulmonologist. This reads like a luxury guide for the insured, not a practical roadmap for the majority.

Don Ablett

The phenotypic distinction is clinically significant but underutilized in practice. The literature consistently demonstrates that phenotype-targeted interventions reduce exacerbation frequency and hospitalization rates. However, the absence of standardized diagnostic algorithms in primary care settings impedes implementation. Further research into accessible biomarkers is warranted to bridge this gap

Chris Ashley

bro i had no idea my coughing fits were bronchitis and not just "bad lungs". i thought it was just me being weak. now i’m gonna ask my doc about carbocisteine. thanks for the wake up call

Eleanora Keene

My mom’s been living with COPD for 12 years. She’s a "blue bloater" through and through. She uses hypertonic saline every morning now-after I read this, I got her a nebulizer. She says it’s the first thing in years that’s actually made breathing easier. This isn’t just info-it’s life-changing. Thank you for writing this.

Ryan Anderson

💯 This deserves to go viral. I’m sharing this with my entire family. My uncle’s on oxygen and never knew why. Now he’s asking his doctor about TMEM16A trials. 🙌 #COPDawareness #PrecisionMedicine

Peter Aultman

Just got my DLCO results-48%. I thought I was just out of shape. Turns out I’m a pink puffer. I quit smoking yesterday. No more excuses.

Ashley Durance

Interesting how this post romanticizes the "pink puffer" as somehow more noble than the "blue bloater." The reality is both are devastating. The language here subtly implies one is more "worthy" of advanced treatment. That’s dangerous. All COPD patients deserve dignity, not categorization.

Scott Saleska

Wait, so if I have both, does that mean I’m a "pink bloater"? Or is that just a myth? I’ve been coughing all winter and can’t walk up stairs without gasping. Which one am I supposed to treat? The article says 85% have both, but doesn’t say how to treat the combo. Anyone know?