When you’re managing diabetes with an insulin pump, every setting matters. A tiny mistake in your basal rate or bolus calculation can send your blood sugar crashing-or soaring-within hours. This isn’t theory. It’s real life for thousands of people using continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII), and getting it right means knowing exactly how your pump works, what each setting does, and how to stay safe when things go wrong.

How Insulin Pumps Actually Work

Insulin pumps don’t replace your pancreas. They’re more like a precise, programmable drip system. Instead of injecting long-acting insulin once a day, you use only rapid-acting insulin-like Humalog or Novolog-delivered through a small tube under your skin. The pump gives you two kinds of insulin: a steady, low background dose (basal) and extra doses (bolus) for meals or high blood sugar.

Modern pumps don’t use long-acting insulins at all. That’s because rapid-acting insulin works fast and fades quickly, which gives you more control. You can adjust your basal rate every hour, turn it up if you’re sick, or drop it before a run. It’s flexibility you can’t get with injections.

But here’s the catch: this flexibility only helps if you set it up right. A pump set wrong can be more dangerous than no pump at all.

Setting Your Basal Rates: The Foundation of Safety

Your basal rate is the silent backbone of your therapy. It’s the insulin your body needs just to keep going-breathing, thinking, digesting-when you’re not eating. Most people need different amounts at different times. Maybe you need more insulin at 3 a.m. because of the dawn phenomenon, or less after your evening walk.

Start by figuring out your total daily insulin dose. Then, split it: 40-50% goes to basal, the rest to boluses. But don’t just divide it evenly. Basal rates usually change every 1-3 hours. A typical profile might look like this:

- 12 a.m. - 4 a.m.: 0.8 units/hour

- 4 a.m. - 8 a.m.: 1.2 units/hour

- 8 a.m. - 12 p.m.: 0.9 units/hour

- 12 p.m. - 6 p.m.: 1.0 units/hour

- 6 p.m. - 12 a.m.: 0.7 units/hour

To test your basal rate, fast for 24 hours. No food, no correction boluses, no exercise. Check your blood sugar every 2-3 hours. If it rises more than 1 mmol/L (18 mg/dL), your basal is too low. If it drops, it’s too high. Do this on different days to find your true pattern.

Dr. John Walsh, author of Pumping Insulin, says the most common pump error? Skipping basal testing. People guess. They don’t test. And then wonder why their numbers are all over the place.

Bolus Settings: Meals, Corrections, and the Hidden Math

When you eat, you need more insulin. That’s the bolus. But it’s not just one number. You need two key settings:

- Insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR): How many units of insulin you need per gram of carbs. A common starting point is 1 unit per 10-15g of carbs, but it varies wildly. One person might need 1 unit per 8g; another might need 1 unit per 20g.

- Insulin sensitivity factor (ISF): How much 1 unit of insulin lowers your blood sugar. For most adults, it’s 1 unit = 2-4 mmol/L (36-72 mg/dL). But if you’re insulin resistant, it could be 1 unit = 1 mmol/L.

Most pumps calculate boluses automatically. You enter your carbs and current blood sugar, and the pump says, “Give 3.2 units.” But if your ICR or ISF is off, the pump will give you the wrong dose every time.

There’s also a third type of bolus: the extended or dual-wave. High-fat meals-like pizza or a creamy pasta dish-digest slowly. A regular bolus spikes insulin too early, then crashes hours later. An extended bolus spreads the dose over 2-4 hours. A dual-wave gives half right away, half over time. Many people don’t use these, and end up with late-night highs.

Infusion Sets and Site Care: Don’t Ignore the Tube

Your pump is only as good as the cannula under your skin. Change your infusion set every 2-3 days. No exceptions. Leaving it in longer? That’s how you get infections, lipohypertrophy (fatty lumps), and blocked lines.

Rotate sites: abdomen, thighs, upper arms, lower back. Don’t reuse the same spot every time. A 2022 study found 27% of new pump users developed lipohypertrophy because they kept injecting in the same place.

Check your site every morning. If it’s red, swollen, painful, or leaking, change it immediately. Even a tiny kink in the tubing can stop insulin flow. And if insulin stops flowing for more than 2 hours, you’re at risk for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). That’s not rare. On Reddit’s r/diabetes, users report DKA developing in just 2-4 hours after an unnoticed disconnection.

Safety Protocols: What to Do When Things Go Wrong

Insulin pumps don’t turn off automatically if you pass out. They keep pumping. That’s why safety isn’t optional-it’s survival.

- Hypoglycemia: If your blood sugar drops and stays low, remove the pump. Treat with glucose tablets or juice. Don’t wait for it to fix itself.

- Hyperglycemia + ketones: If your blood sugar is above 14 mmol/L (250 mg/dL) and you have ketones, don’t just bolus more. Check your infusion set. Replace it. Flush the tubing. If ketones don’t drop in 2 hours, call your doctor.

- During surgery: For minor procedures where you’ll eat soon, you can keep the pump on-if your site is accessible and your glucose is between 4-12 mmol/L. For major surgery? Stop the pump. Switch to IV insulin.

- Postpartum: After giving birth, insulin needs drop sharply. Many women need to reduce their basal rate by 10-20% right away. If you’re breastfeeding, you might need to cut it even more.

The NIH warns: if someone using a pump becomes unconscious, treat it like a medical emergency. They need help fast-because the pump doesn’t know they’re down.

Advanced Features and New Tech

Modern pumps aren’t just pumps anymore. The Medtronic MiniMed 670G and Tandem Mobi are hybrid closed-loop systems. They adjust basal insulin automatically based on your CGM readings. But they still need you to tell them when you eat. They’re not magic.

The Omnipod 5 works with multiple CGMs, not just one brand. That’s a big deal. You’re not locked into one system anymore.

The Tandem Mobi, released in 2023, is the smallest pump on the market-about the size of a large coin. It’s designed for kids, with big buttons and simple menus. But even the simplest pump needs proper setup.

Next up? Bihormonal pumps that deliver both insulin and glucagon. They’re still in trials. But they could be the closest thing to an artificial pancreas we’ve seen.

Training and Real-World Challenges

You can’t just get a pump and go. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists says you need at least 15 hours of structured training before starting. That includes:

- How to insert a cannula

- How to program basal rates

- How to calculate boluses

- How to troubleshoot alarms

- How to handle emergencies

Most people get the basics in 2-4 weeks. But mastering extended boluses, temporary basals, and insulin-on-board (IOB) calculations? That takes 3-6 months.

And the biggest hurdle? Carbohydrate counting. A 2021 study found 38% of high blood sugar episodes in pump users were caused by miscounting carbs. You can have the best pump in the world, but if you think a slice of bread is 10g of carbs when it’s actually 25g, you’re going to be in trouble.

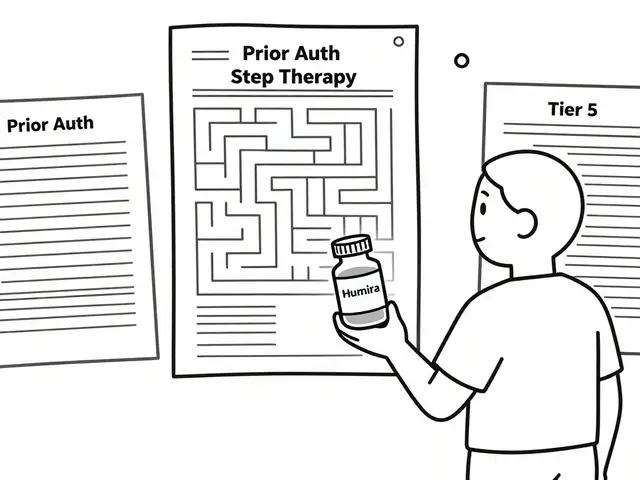

Cost, Access, and the Future

In the U.S., insulin pump therapy costs $6,500-$8,200 a year. That’s pump, supplies, and insulin. Multiple daily injections? $4,800-$5,500. Insurance helps, but gaps remain.

Adoption is growing. About 30% of people with type 1 diabetes in the U.S. use pumps. Among teens and young adults? It’s 45%. For those over 65? Only 22%. The gap isn’t just about tech-it’s about support. Older adults often lack the training or help they need.

By 2028, the American Diabetes Association predicts 40% of type 1 patients will be on pumps. But that won’t happen unless access and education improve.

What You Need to Do Today

If you’re on a pump:

- Test your basal rate this week. Fast for 24 hours. Track your numbers.

- Check your infusion set. Is it older than 72 hours? Change it.

- Review your ICR and ISF. Are they based on real data-or just a guess?

- Carry backup: extra infusion sets, insulin, batteries, glucose tabs.

- Know your emergency plan. If you can’t reach your care team, who do you call?

If you’re thinking about starting:

- Get trained. Don’t skip it.

- Ask for a pump educator who’s seen hundreds of patients.

- Don’t believe the hype. Pumps aren’t easy. They’re powerful-but they demand your attention.

Insulin pumps give you freedom. But freedom comes with responsibility. Get the settings right. Stay vigilant. Your next meal, your next night’s sleep, your next day-all of it depends on it.

Can I use an insulin pump if I have type 2 diabetes?

Yes, but only if you’re insulin-requiring and your diabetes is unstable. The American Diabetes Association recommends pumps for type 2 patients who need tight control and can manage the technology. This includes people with high insulin needs, unpredictable blood sugar swings, or those who struggle with multiple daily injections. It’s not for everyone with type 2-only those who truly benefit from the flexibility and precision of pump therapy.

How often should I change my infusion set?

Every 2 to 3 days. Leaving it in longer increases the risk of infection, lipohypertrophy (fatty tissue buildup), and blocked insulin flow. Even if the site looks fine, insulin absorption drops after 72 hours. Always rotate sites-abdomen, thighs, arms, lower back-and never reuse the same spot within a week.

What should I do if my pump stops working?

First, check for obvious issues: empty reservoir, kinked tubing, air bubbles. Replace the infusion set immediately. If you’re still not sure, give yourself a correction bolus using a pen or syringe based on your ISF. Never wait. If your blood sugar rises above 14 mmol/L (250 mg/dL) and you have ketones, treat it like a medical emergency. Contact your care team or go to urgent care. Your pump is a tool-not a backup. Always have insulin and syringes on hand.

Can I swim or shower with my insulin pump?

Most modern pumps are water-resistant but not waterproof. You can shower with them, but avoid submerging them in water. For swimming, bathing, or water sports, disconnect the pump. You can safely disconnect for up to 1 hour. If you’re in water longer, give yourself a bolus with a pen before disconnecting, and check your blood sugar after getting out. Some pumps have waterproof cases or detachable tubing options-ask your supplier.

Why do I keep getting high blood sugar after meals even with a bolus?

It’s likely your insulin-to-carb ratio is too high (you’re not giving enough insulin), or you’re not using an extended bolus for slow-digesting meals. Foods high in fat or protein-like pizza, pasta with cream sauce, or burgers with cheese-delay carb absorption. A regular bolus spikes insulin too early, then your blood sugar rises hours later. Try a dual-wave or extended bolus over 2-4 hours. Also, check your site. A blocked cannula can cause delayed insulin delivery.

Is it safe to use a pump during pregnancy?

Yes, and many endocrinologists recommend it. Pregnancy increases insulin needs dramatically, especially in the second and third trimesters. Pumps allow precise, flexible dosing that injections often can’t match. Basal rates may need to be increased by 50-100% as pregnancy progresses. After delivery, insulin needs drop sharply-often by 30-50%. Close monitoring and frequent adjustments are critical. Work with a diabetes and pregnancy specialist.

Do insulin pumps have alarms for low or high blood sugar?

Not directly. Pumps don’t sense blood sugar unless they’re paired with a continuous glucose monitor (CGM). If you have a CGM linked to your pump, it can alert you to highs and lows, and some systems (like the MiniMed 670G) can automatically suspend insulin delivery if your glucose drops too low. But if you’re not using a CGM, the pump only alarms for technical issues-low battery, blocked line, empty reservoir. You still need to check your blood sugar manually at least four times a day.

What’s the biggest mistake new pump users make?

They assume the pump will fix everything. It won’t. The biggest mistake is not learning how to use it properly. Skipping basal testing, guessing carb counts, ignoring site changes, and not carrying backup supplies. A pump doesn’t think for you. It follows your settings. If your settings are wrong, your blood sugar will be wrong. Success comes from discipline-not technology.

Insulin pumps are powerful tools-but they’re not magic. They require knowledge, discipline, and constant attention. Get the settings right. Test often. Change your site. Know your limits. And never stop learning.

Geethu E

Just switched to a pump last month and this post saved my life. I was guessing my basal rates like an idiot-now I’m fasting for 24 hours this weekend to test mine. No more guessing. No more 3 a.m. crashes.

Also, changing my site every 48 hours? Game changer. Used to leave it in for 5 days because I was lazy. Now I’m paranoid in the best way.

jaya sreeraagam

I can’t believe how many people treat their insulin pump like a magic box that just ‘works’-it’s not a toaster, it’s a precision medical device that demands your attention every single day. I’ve been on pumps for 14 years, and the biggest mistake I see is people ignoring their ICR and ISF because they ‘feel fine.’ Feeling fine doesn’t mean your numbers are right. I had a patient last year who thought her 1:15 ratio was fine until she started having ketoacidosis every other week-turns out she was under-dosing by 40% because she was using a ratio from 2018. Update your settings. Test. Track. Don’t just hope.

And please, for the love of all things glucose, change your infusion set every 2-3 days. Lipohypertrophy isn’t cute. It’s a nightmare that ruins absorption and makes your life hell. Rotate. Rotate. Rotate.

doug schlenker

Biggest thing I learned after my first DKA scare? Always carry backup. I used to think, ‘Oh, I’ve got my pump, I’m fine.’ Then I got a kinked tube on a hike, didn’t notice for 3 hours, and woke up in the ER. Now I have a pen, syringes, and a vial of insulin in my backpack at all times-even to the grocery store.

Also, extended boluses for pizza? Life-changing. I used to crash at 2 a.m. every Friday night. Now I do a dual-wave. No more 3 a.m. panic.

Nicola Mari

It’s appalling how casually people treat something as life-or-death as insulin delivery. You’re not a gamer tweaking settings for XP-you’re managing a biological system that will kill you if you’re lazy. I’ve seen people leave their infusion sets in for 10 days. Ten days. That’s not a mistake. That’s negligence. And then they wonder why they’re in the hospital. No one’s coming to save you. Your pump doesn’t care. Your blood sugar doesn’t care. You do. Or you die. Simple.

Alexis Mendoza

Why do we even use insulin pumps if we’re still doing all this math ourselves? It feels like we’re just giving the computer more work to do. Like, if it can adjust basals based on CGM, why can’t it learn my carb habits too? Why do I still have to tell it I’m eating pizza?

I get it’s not AI yet, but… shouldn’t it be smarter?

Chris Kahanic

As someone who’s been on insulin therapy for over 25 years, I can confirm that the fundamentals outlined here are still the bedrock of safe pump use. The technology has advanced, but human behavior has not.

The most dangerous assumption remains: ‘I don’t need to test my basal rate because I feel okay.’ This is a myth that kills. Testing is non-negotiable. Period.

Also, the recommendation to carry backup supplies is not optional. It is a survival protocol. Treat it as such.

anant ram

Just want to add: if you’re using a dual-wave bolus, always set the extended portion to match your meal’s fat content. Pizza? 3 hours. Mac and cheese? 2.5 hours. Fried chicken? 4 hours. Don’t just wing it. And if your pump doesn’t let you set custom extended durations, get a better pump. You deserve better than guesswork.

Also-change your site on the same day every time. I do it every Monday and Thursday. No exceptions. No excuses.

king tekken 6

Man, I just realized something-pumps are basically like a robot that’s always yelling at you to do stuff. ‘Change your site!’ ‘Test your basal!’ ‘Did you count the carbs?!’

It’s like having a helicopter parent that also happens to be a nurse.

And the worst part? It doesn’t even let you skip days. Even when you’re drunk. Even when you’re sick. Even when you just want to sleep.

But… I guess it works. So I guess I’m stuck with my little insulin robot.

Still, why can’t it just read my mind? I’m tired.

DIVYA YADAV

They say pumps are ‘freedom’-but freedom for who? The companies that sell them? The doctors who get paid for the training? Meanwhile, people in India can’t even get insulin at a fair price, and here we’re arguing about dual-wave boluses like it’s a luxury.

They want us to believe this tech is the answer-but what about the people who can’t afford the pump, the supplies, the CGM, the training? This isn’t progress. It’s exclusion dressed up as innovation.

And don’t get me started on how they market this to kids like it’s a video game. ‘Look, your blood sugar is a number! Press buttons to fix it!’ It’s not a game. It’s a prison with a screen.

Kim Clapper

I’m sorry, but I have to say this: the entire premise of this post is dangerously oversimplified. You assume everyone has access to a CGM, a pump, a diabetes educator, and the time to fast for 24 hours. What about single parents working two jobs? What about people without health insurance? What about those who live in food deserts and can’t even get accurate carb counts?

And let’s not pretend that ‘testing your basal’ is something everyone can do safely. Hypoglycemia isn’t a ‘learning experience’-it’s a medical emergency.

This post reads like it was written by someone who’s never missed a meal, never been denied care, never had to choose between insulin and rent.

It’s not just unhelpful-it’s tone-deaf.

Bruce Hennen

Infusion set changes every 48 hours are non-negotiable. Period. The data is clear: insulin absorption declines by 25% after 72 hours. That’s not anecdotal. That’s peer-reviewed.

Also, the claim that ‘most people’ need 40-50% basal is misleading. For some, especially those with insulin resistance, it’s 60%. You can’t generalize. Test. Your numbers. Not someone else’s.

Jake Ruhl

Okay but… what if the pump is just… wrong? Like, what if the whole system is a scam? What if insulin isn’t even the problem? What if it’s the food industry? The pharmaceutical companies? The FDA? I mean, why do we even need pumps? Why not just eat less sugar? Why not just… believe in God?

I heard a guy on YouTube say insulin is just a way to keep people dependent. Like, think about it-why would they let us cure diabetes? They make billions off it.

Also, I tried a pump once. It beeped too much. So I stopped. Now I just drink lemon water and pray. My sugar’s fine. Maybe the pump was the problem?

Just saying… maybe we’re all being manipulated.