Aminoglycoside Ototoxicity Risk Calculator

How This Tool Works

This calculator helps determine your risk of developing permanent hearing and balance loss from aminoglycoside antibiotics based on key risk factors identified in medical research. Your results will be shown as low, medium, or high risk, along with personalized recommendations.

Important: This tool is for informational purposes only. Always consult with your healthcare provider before making treatment decisions.

Risk Factors

Your Risk Assessment

Every year, hundreds of thousands of people receive aminoglycoside antibiotics to fight life-threatening infections like sepsis, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, and serious urinary tract infections. These drugs work fast and well - but for many, the cost is permanent. Aminoglycoside ototoxicity doesn’t just cause temporary ringing in the ears. It destroys hearing and balance cells in the inner ear, often without warning. And once gone, those cells don’t come back.

What Exactly Is Aminoglycoside Ototoxicity?

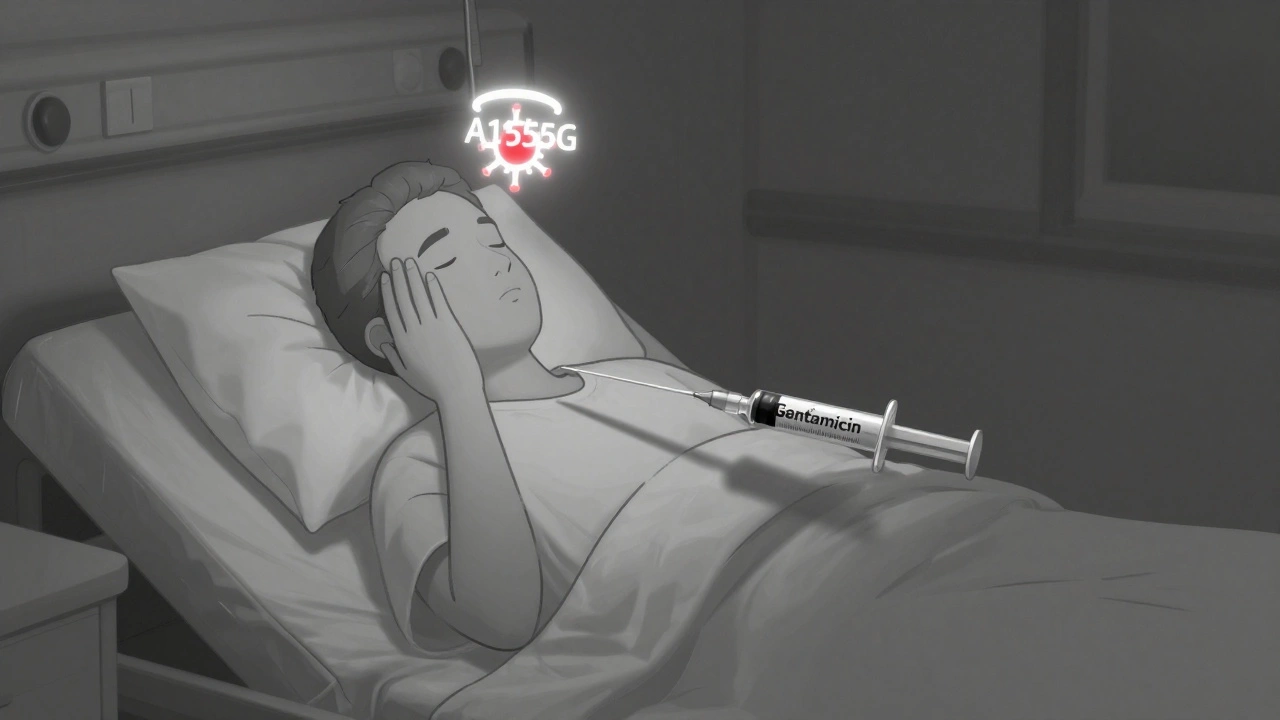

Aminoglycoside ototoxicity is damage to the inner ear caused by antibiotics like gentamicin, amikacin, tobramycin, and streptomycin. These drugs were developed in the 1940s and remain vital tools in hospitals today, especially when other antibiotics fail. But they don’t just target bacteria. They also slip into the inner ear, where they kill sensory hair cells - the tiny structures that turn sound and head movement into electrical signals your brain understands.Unlike some side effects that fade after stopping the drug, this damage is permanent. The hair cells in your cochlea (for hearing) and vestibular system (for balance) die and don’t regenerate in humans. That’s why many patients wake up weeks after treatment with hearing loss, dizziness, or trouble walking in the dark - and it never improves.

How Common Is It?

Studies show between 20% and 47% of patients who get aminoglycosides develop some level of hearing loss. In high-risk groups - like those with kidney disease, older adults, or people with certain genetic mutations - the rate can be even higher. Vestibular damage (affecting balance) happens in 15% to 30% of cases. That’s not rare. That’s a major risk.One study of 217 patients found that 89% weren’t warned about this risk before treatment. Many didn’t know antibiotics could cause deafness. By the time they noticed their hearing was fading, it was too late.

Why Does This Happen?

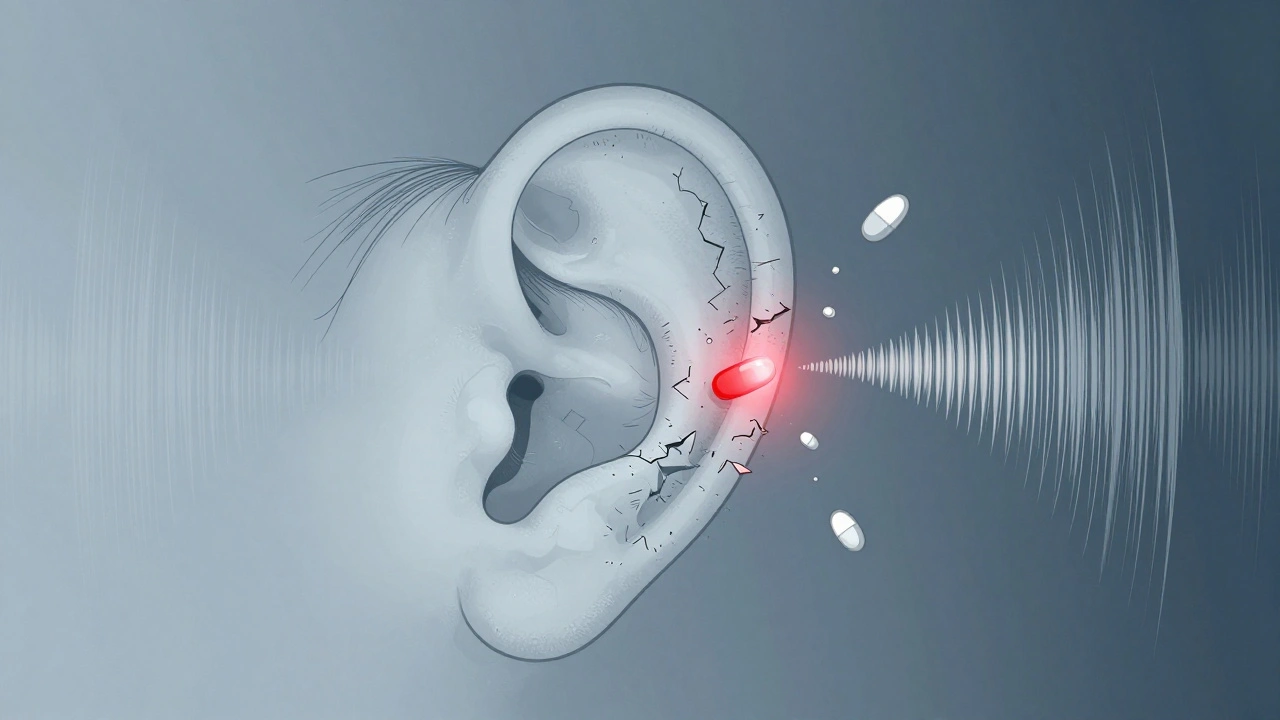

Aminoglycosides enter the inner ear through the bloodstream, crossing a barrier called the blood-labyrinth barrier. Once inside, they bind to receptors on hair cells and trigger a chain reaction. The drugs activate NMDA receptors, which flood cells with nitric oxide. That leads to oxidative stress - essentially, the cells drown in their own toxic waste. Free radicals form, mitochondria (the cell’s power plants) fail, and the hair cells die through both apoptosis (programmed death) and necrosis (violent cell rupture).Genetics play a huge role. Some people carry a mutation in their mitochondrial DNA - specifically the A1555G or C1494T variants - that makes their hair cells extra vulnerable. These mutations are rare in the general population, but if you have them, even a single dose of gentamicin can cause deafness. In fact, the T1095C mutation increases gentamicin-induced cell death by 47% compared to normal cells.

And it’s not just the drug. Noise exposure before or during treatment makes things worse. Loud sounds - even a concert or construction noise - can boost ototoxicity by up to 52%. Inflammation from infections like sepsis also helps the drug leak into the inner ear faster, increasing damage by 63% in animal models.

How Is It Different From Other Drug-Induced Hearing Loss?

Cisplatin, a chemotherapy drug, also causes hearing loss - but it’s different. Cisplatin hits the lower frequencies first and mostly affects the cochlea. Aminoglycosides start at the top - the high frequencies - and damage both hearing and balance. That’s why patients often report trouble hearing children’s voices, birds chirping, or beeps from alarms before they notice low-pitched sounds.Also, while cisplatin mainly causes apoptosis, aminoglycosides trigger both apoptosis and necrosis. That means the damage is more violent and widespread. And unlike cisplatin, aminoglycosides can cause sudden vestibular loss - meaning you lose your sense of balance entirely. One case from Johns Hopkins documented a 34-year-old who developed total bilateral vestibular failure after just 10 days of gentamicin. He spent 14 months in rehab learning to walk again.

Who’s Most at Risk?

You’re at higher risk if you:- Have a family history of unexplained hearing loss

- Are over 65

- Have kidney disease (aminoglycosides are cleared by the kidneys)

- Are receiving high doses or long courses (over 7 days)

- Have existing high-frequency hearing loss (you’re 3.2 times more likely to lose more hearing)

- Are being treated for multidrug-resistant TB (68% of ototoxicity cases occur here)

- Are exposed to loud noise during treatment

- Carry the A1555G or C1494T mitochondrial mutation

Many of these risk factors are hidden. You might not know you have the mutation until it’s too late. That’s why genetic screening is becoming critical.

Can You Prevent It?

Yes - but only if you’re monitored closely. The biggest problem? Most hospitals don’t do it.Only 37% of U.S. hospitals have formal ototoxicity monitoring protocols. In low-income countries, that number drops to 18%. But the tools exist:

- High-frequency audiometry: Standard hearing tests check 0.25-8 kHz. High-frequency tests go up to 16 kHz and catch damage 5-7 days earlier.

- Therapeutic drug monitoring: Checking blood levels of the drug (peak and trough) reduces risk by 28%.

- OtoSCOPE® genetic test: This test screens for the A1555G and C1494T mutations with 94.7% accuracy. If you test positive, doctors can avoid aminoglycosides entirely.

- Baseline testing: The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association recommends testing hearing and balance within 24 hours of starting treatment, then every 48-72 hours.

Some hospitals use these tools. Most don’t. Patients often get the drug first and find out about the damage weeks later - when it’s irreversible.

What’s Being Done to Stop It?

Researchers are racing to find solutions. One promising drug, ORC-13661, is in Phase II trials. When given with amikacin, it preserved 82% of hair cells in patients. It’s been granted Fast Track status by the FDA - meaning approval could come within a few years.Other approaches include:

- Transtympanic injections: Delivering protective compounds directly into the middle ear to block the drug from reaching hair cells. Early trials show 25-30 dB of hearing preservation.

- Gene therapy: The Hearing Restoration Project is testing ways to correct mitochondrial mutations before treatment. In mice, this cut ototoxicity by 67%.

- Pharmacogenomics: Matching the right drug to the right patient based on genetics. Experts predict this could reduce ototoxicity by 50-70% in the next decade.

But these advances won’t help the 80% of aminoglycoside use happening in places without labs, genetic tests, or trained audiologists.

What Patients Should Know

If you’re being prescribed an aminoglycoside:- Ask: “Is there a safer alternative?”

- Ask: “Can you test my hearing before and during treatment?”

- Ask: “Can you check for the A1555G mutation?”

- Ask: “Will you monitor my drug levels?”

- Avoid loud noise - concerts, power tools, even loud TVs - during treatment.

- Report ringing, muffled hearing, or dizziness immediately - even if you think it’s normal.

Don’t assume your doctor knows. A 2021 survey of doctors found many still underestimate how common and severe this side effect is. You have to be your own advocate.

What Happens After the Damage Is Done?

There’s no cure. But there’s help.For hearing loss: Hearing aids can help, especially for high-frequency loss. Cochlear implants may be an option if the damage is severe.

For balance loss: Vestibular rehabilitation therapy (VRT) is essential. It retrains your brain to rely on vision and body sense instead of the inner ear. Many patients regain function - but rarely to pre-treatment levels. One patient from the Hearing Loss Association of America described it as “learning to walk again after a stroke.”

Tinnitus - the constant ringing - affects 63% of patients. It’s often the most persistent symptom. Sound therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and masking devices can help manage it.

But none of this fixes the damage. That’s why prevention is everything.

The Bigger Picture

Aminoglycosides are a lifeline in the fight against antibiotic resistance. But we’re using them like blunt tools. We treat everyone the same, even though some people are genetically wired to be destroyed by them.The FDA now requires black box warnings on all aminoglycosides. The European Medicines Agency says genetic screening is required for long-term use. But implementation? That’s where the system fails.

Until every hospital - in every country - tests for risk before giving these drugs, people will keep losing their hearing. Not because the drugs are evil. But because we haven’t made prevention a priority.

The science is here. The tools are here. What’s missing is the will.

Gilbert Lacasandile

Just had a cousin go through this after a sepsis scare. They gave her gentamicin without a word about hearing risk. She woke up with tinnitus and couldn’t hear her daughter’s voice for weeks. Now she’s got hearing aids and balance therapy. It’s insane we don’t screen people before dumping these drugs into them.

Why is this still not standard? We test for everything else.

Michael Robinson

It’s not the drug that’s evil. It’s the system that treats people like test subjects instead of humans with unique bodies.

We fix cars with manuals. Why don’t we fix people the same way?

Andrea Petrov

Let’s be real - this isn’t an accident. Big Pharma knows about the A1555G mutation. They’ve known for decades. But if they start screening everyone, they lose billions in sales.

They’d rather let people go deaf than lose a single dollar.

And don’t tell me it’s ‘cost-prohibitive.’ We fund wars and space rockets. But a $50 genetic test? Too expensive.

Wake up. This is profit over people. Always has been.

Suzanne Johnston

I’ve worked in ICU for 18 years. I’ve seen this happen too many times.

The worst part? Nurses and residents often don’t even know the risks. They’re just following orders.

We need mandatory training on ototoxicity in med school - not as an afterthought, but as core curriculum.

And we need to empower patients to ask. No one should leave the ER thinking, ‘I didn’t know antibiotics could steal my hearing.’

It’s not just medical. It’s moral.

Let’s make prevention the default, not the exception.

Haley P Law

MY BEST FRIEND WENT DEAF AFTER A SIMPLE UTI.

They gave her tobramycin. No warning. No test. Just ‘you’ll be fine.’

Now she cries every time she hears birds. She can’t hear her own dog bark.

WHY ISN’T THIS ON THE NEWS??

Someone please start a petition. I’m so mad I can’t even type straight 😭

Nikhil Pattni

Look, I’m from India and we use aminoglycosides like candy here - especially in rural clinics where there’s no audiologist within 200 km. But the problem isn’t just genetics or lack of screening - it’s the entire antibiotic-overuse culture.

Doctors prescribe them because they’re cheap, fast, and work. They don’t have time to wait for cultures. They don’t have labs to check levels. And patients? They’re happy to get a shot that ‘fixes’ them fast.

But here’s the real issue: we’re not educating the public. No one tells them, ‘Hey, this might make you deaf.’ Why? Because then they’d refuse the drug. And if they refuse, the infection kills them.

It’s a lose-lose. So we keep doing the same thing and pretending it’s not broken.

Until we fix the healthcare infrastructure - not just the drug policy - this will keep happening. Genetic tests won’t help if no one can afford them. Monitoring won’t help if no one’s trained to do it. We need systemic change, not just fancy new drugs.

Arun Kumar Raut

I get why people are angry. But let’s not forget - these drugs save lives.

My sister had MDR-TB. Without amikacin, she’d be dead.

She lost her high-frequency hearing. It sucks. But she’s alive.

Maybe the answer isn’t to stop using them - but to make sure every hospital has a basic hearing test kit and a checklist before giving the drug.

It’s not about being perfect. It’s about being better than we are now.

Let’s push for simple, cheap fixes - not just outrage.

precious amzy

One must question the epistemological foundations of contemporary otological interventionism.

Is the human ear not a metaphysical vessel of perception, rendered vulnerable by the technocratic hegemony of pharmaceutical empiricism?

That the FDA mandates a black box warning - yet permits continued mass administration - reveals a profound ontological contradiction: we acknowledge the harm, yet institutionalize its propagation.

One wonders: is ototoxicity not merely the inevitable consequence of a civilization that commodifies biological integrity?

Perhaps the real cure lies not in ORC-13661, but in the deconstruction of the medical-industrial complex itself.

Carina M

It is unconscionable that any medical professional would administer a drug with such a well-documented, irreversible, and preventable side effect without first conducting genetic screening. The fact that this is not standard practice in 82% of U.S. hospitals constitutes gross negligence.

Patients are not experimental subjects. They are entitled to informed consent - not a post-hoc realization that their cochlea has been chemically incinerated.

This is not a tragedy. It is a systemic moral failure. And those who continue to defend the status quo are complicit.

William Umstattd

Let me be perfectly clear: if your hospital gives aminoglycosides without baseline audiometry, therapeutic drug monitoring, and genetic screening - they are not practicing medicine. They are practicing malpractice.

There is no excuse. Not in 2025. Not in a country with the resources of the U.S.

I’ve reviewed the literature. I’ve spoken to otologists. I’ve seen the data. This is not a gray area. It’s black and white.

Every time a patient loses their hearing to this, someone in a white coat failed them.

And if you’re reading this and you work in a hospital - demand change. Or get out.

Angela R. Cartes

Wow. So much drama. 😴

People get antibiotics. Sometimes they lose hearing. Sometimes they don’t.

It’s not like we’re giving them poison on purpose.

Maybe just… don’t take them unless you really need them? 🤷♀️