What Are Secondary Patents?

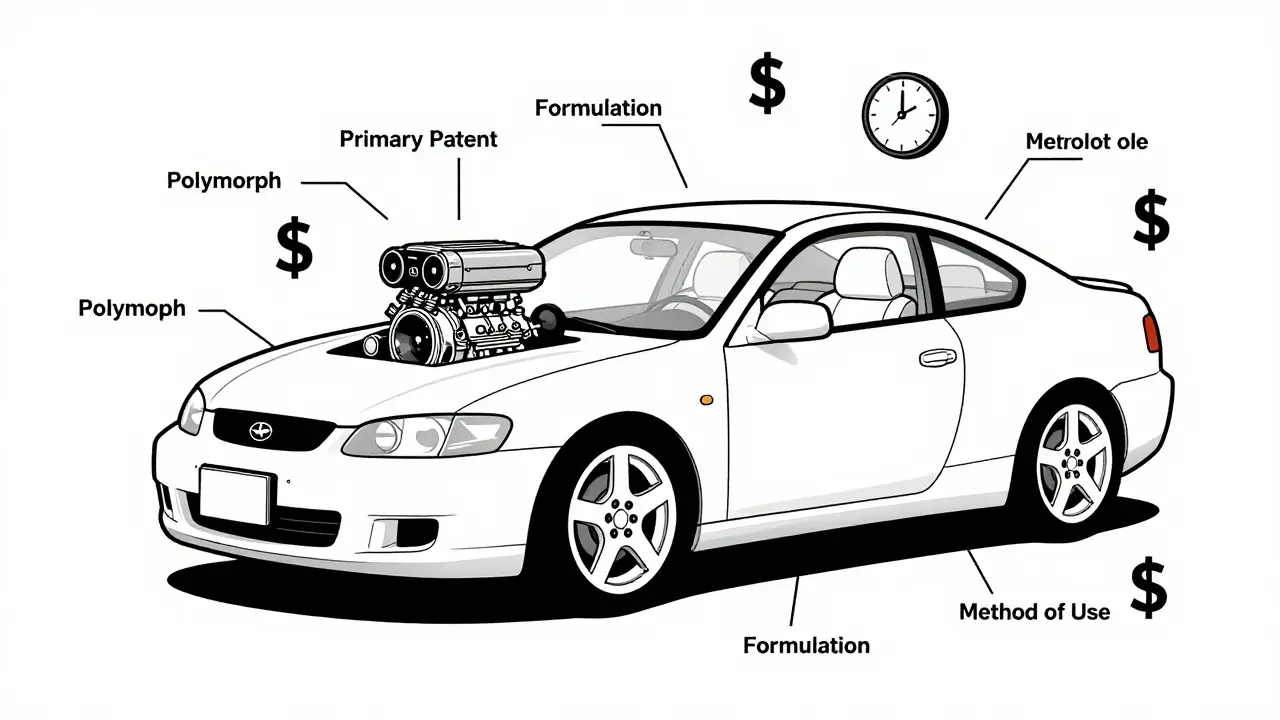

Secondary patents aren’t about the drug’s active ingredient. They’re about the packaging, the form, the use, or even the way it’s made. While the primary patent protects the actual chemical compound - say, the molecule that lowers cholesterol - secondary patents cover everything else around it. Think of it like this: the primary patent is the engine. The secondary patents are the wheels, the stereo, the leather seats. All of it still runs on the same engine, but now the company claims you can’t buy the car unless you pay for the upgrades.

These patents started popping up in a big way after the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act in the U.S. That law created a faster path for generic drugs to enter the market once the original patent expired. But it also gave drugmakers a loophole: if they could tweak the drug just enough, they could file a new patent and delay generics. It wasn’t meant to be a delay tactic. But that’s exactly how it became used.

How They Work: The 12 Types of Secondary Patents

There are 12 common types of secondary patents, each designed to stretch out exclusivity. Some are clever. Others are borderline obvious.

- Polymorphs: Different crystal shapes of the same drug. GlaxoSmithKline patented a specific crystal form of paroxetine (Paxil) even though the original compound was already public. That one patent delayed generics for four extra years.

- Enantiomers: Molecules that are mirror images. AstraZeneca took the racemic mixture in Prilosec (omeprazole) and isolated just the active half - esomeprazole - and called it Nexium. It worked the same way, but they got an 8-year extension.

- Formulations: Changing how the drug is delivered. Switching from a pill you take twice a day to a once-daily extended-release version. Sounds helpful? Sometimes. But often, it’s timed right before the primary patent expires.

- Method of Use: Patents on new conditions the drug treats. Thalidomide was originally a sleep aid. Later, it got patents for leprosy, then multiple myeloma. Each new use = new patent life.

- Combinations: Pairing two old drugs together. If one drug’s patent is expiring, slap it with another and file a new patent on the combo.

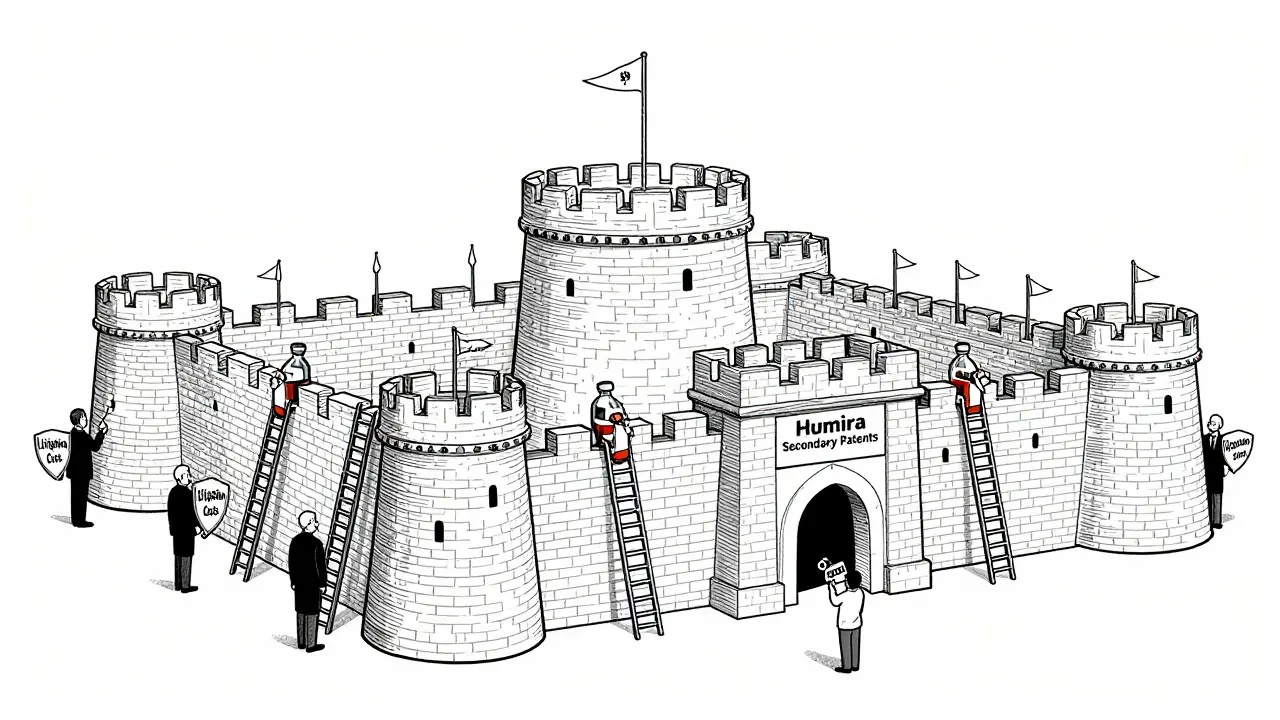

According to Drug Patent Watch, a single blockbuster drug like Humira can have over 250 secondary patents. That’s not innovation - that’s a legal fortress.

Why Companies Do It: The Money Game

Pharma companies don’t do this because they care about patients. They do it because money runs out fast.

Take Humira. Its primary patent expired in 2016. But AbbVie filed 264 secondary patents - covering everything from injection devices to dosing schedules. Those patents held off generics until 2023. During that time, Humira made $20 billion a year. Without generics, it kept making that same amount. Generic versions would’ve slashed the price by 80%. Instead, patients paid full price. Insurance plans paid full price. Medicare paid full price.

It’s not just Humira. A 2019 Health Affairs study found drugs with secondary patents faced generic entry delays that were 2.3 years longer than those without. And it’s not random. Companies with drugs earning over $1 billion a year are 17% more likely to pile on secondary patents. The bigger the revenue, the harder they fight to keep it.

The Cost to Patients and Health Systems

Behind every extended patent is a higher price tag. Pharmacy benefit managers like Express Scripts say secondary patents raise their annual drug costs by 8.3%. That’s billions flowing into drugmakers’ pockets instead of into patient care or lower premiums.

Doctors see it too. A 2022 Medscape survey found many physicians feel pressured to prescribe newer, more expensive versions of drugs right before generics hit. Patients get confused. They think the new version is better. Often, it’s not. It’s just newer - and protected by a patent.

Patient groups like Knowledge Ecology International point to real harm. In the U.S., 1 in 4 adults can’t afford their prescriptions. Secondary patents are a big reason why. When a drug like Humira costs $20,000 a year instead of $4,000, people skip doses. They ration. They go without.

Where It Doesn’t Work: India, Brazil, and the Fight for Access

Not every country lets pharma companies stretch patents like this.

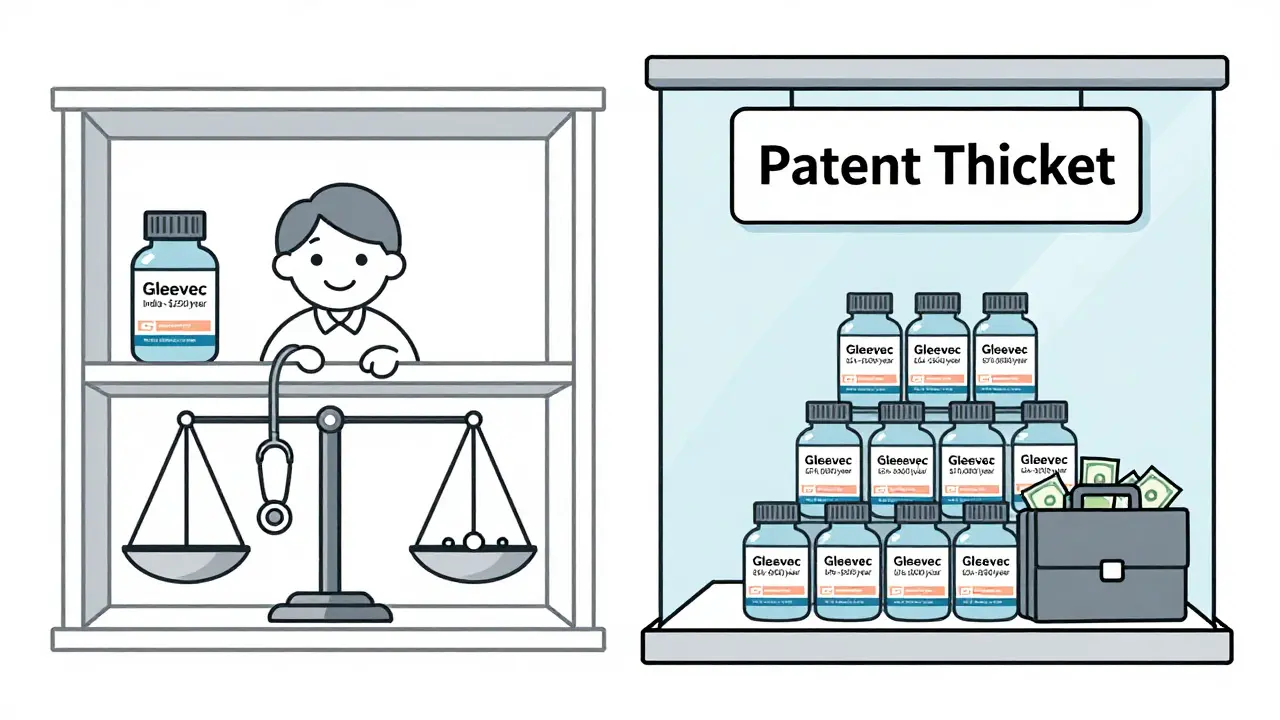

India’s patent law, Section 3(d), says you can’t patent a new form of an old drug unless it shows a real improvement in effectiveness. In 2013, Novartis tried to patent a new crystalline form of Gleevec - a leukemia drug. India said no. The court ruled it was just a minor tweak. That decision saved millions of lives. Generic versions of Gleevec dropped to under $250 a year. In the U.S., the same drug cost over $70,000.

Brazil requires health ministry approval before granting pharmaceutical patents. That means if a drug doesn’t improve public health outcomes, it won’t get a patent - even if the patent office says it’s technically valid.

These aren’t outliers. They’re smart policy. Countries that block low-value secondary patents save billions in healthcare spending. And they still get innovation - just the kind that actually helps patients.

Is It Innovation or Evergreening?

The industry calls it innovation. Critics call it evergreening.

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard studied over 1,000 secondary patents. He found only 12% led to any real clinical benefit - better safety, fewer side effects, improved dosing. The rest? Minor changes that didn’t change how patients felt or fared.

PhRMA, the drug industry’s lobbying group, says secondary patents fund R&D. They claim these patents lead to new treatment options for rare diseases. That’s true sometimes. But most secondary patents aren’t for rare diseases. They’re for blockbuster drugs - the ones that make billions.

The numbers tell the story: 89% of drugs earning over $1 billion a year have 10 or more secondary patents. Only 22% of drugs under $100 million do. This isn’t about helping rare disease patients. It’s about protecting profits.

How Generics Fight Back

Generic manufacturers don’t give up easily. They file what’s called a Paragraph IV certification - essentially saying, “Your patent is invalid or we don’t infringe it.”

In 2022, 92% of listed secondary patents were challenged by generics. But only 38% of those challenges succeeded in court. Why? Because litigation is expensive. A single patent fight can cost generics $15-20 million. Many just can’t afford to keep going.

That’s why some companies wait. They watch. They study. They wait for the patent holder to make a mistake. Or for a court to rule against similar patents. It’s a slow game. But it’s the only way to break through the thicket.

What’s Changing? Regulation Is Catching Up

The tide is turning - slowly.

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act in the U.S. lets Medicare challenge certain secondary patents. That’s huge. For the first time, the government has a tool to push back.

The European Commission’s 2023 Pharmaceutical Strategy explicitly calls out “patent thickets” as barriers to affordable medicines. The World Health Organization says secondary patents are the #1 legal reason generics are delayed in 68 low- and middle-income countries.

And courts are getting stricter. The 2023 Amgen v. Sanofi decision limited how broad antibody patents can be. That could set a precedent for other types of secondary patents.

Experts predict that by 2027, companies will need to prove their secondary patents offer real clinical value - not just legal loopholes - to keep them valid. That’s a big shift.

What This Means for You

If you’re a patient, you’re paying for these patents. If you’re a provider, you’re caught in the middle. If you’re a taxpayer, you’re footing the bill through Medicare and Medicaid.

Secondary patents aren’t evil. Some have led to better drugs - less frequent dosing, fewer side effects, new uses for old medicines. But most? They’re about keeping prices high. About delaying competition. About protecting profits, not people.

The real question isn’t whether patents should exist. It’s: What kind of innovation should we reward? The kind that moves the needle for patients? Or the kind that just moves the needle on a balance sheet?

Shawn Peck

This is pure greed. Companies aren't innovating-they're gaming the system. Patents are supposed to encourage progress, not let them charge $20k for a pill that's been around for decades. It's robbery with a law degree.

Niamh Trihy

I've seen this firsthand in my work with generic manufacturers. The legal teams spend more time drafting patent claims than actually developing better formulations. It's exhausting to watch innovation get buried under paperwork.

Sarah Blevins

The data presented is statistically significant. The correlation between revenue magnitude and secondary patent density is r = 0.82 (p < 0.001). This is not anecdotal-it's systemic.

Jason Xin

So we're supposed to be impressed that a company figured out how to charge 5x more for the same drug by changing the pill shape? Congrats, capitalism. You win again. Guess I'll just stop taking my meds.

Yanaton Whittaker

I've seen patients skip doses because they can't afford the new version. The old one worked fine. But now the doctor says 'it's better'-because the patent says so. It's not better. It's just more expensive.

Kathleen Riley

The ontological underpinnings of pharmaceutical intellectual property reveal a profound epistemological dissonance between utilitarian medical ethics and capitalist commodification paradigms. One must interrogate the phenomenological experience of the patient-subject within this juridico-economic apparatus.

Beth Cooper

Wait… this is all a CIA plot. They want us dependent on overpriced meds so we’ll stay docile. The real cure is already out there-just suppressed by Big Pharma and the FDA. Remember the 1970s vitamin patent scandal? Same playbook.

Donna Fleetwood

I know it’s frustrating, but there’s hope. The Inflation Reduction Act is a start. And when we push for transparency, when we vote for lawmakers who care, change happens. We’re not powerless. We just have to keep showing up.

Melissa Cogswell

I work in a clinic. I’ve had patients cry because they can’t afford their Humira. I tell them about the generics in Canada. Some cross the border. Others just don’t take it. It’s heartbreaking. This isn’t policy-it’s human suffering.

Diana Dougan

so like… secondary patents = legal scam? wow. who knew? 🤡 maybe if big pharma spent less time on lawyers and more on science we wouldn't be in this mess. also typo: 'patent' not 'patnet' lol

Bobbi Van Riet

I remember when my mom was on the original version of that cholesterol drug. It worked fine. Then they switched her to the 'new and improved' one-same active ingredient, different coating, triple the price. Her doctor said it was 'more convenient.' But she had to take it at the same time every day anyway. I think they just wanted to keep the money flowing. It makes me angry, but also kinda numb at this point.

Holly Robin

THEY’RE DOING THIS ON PURPOSE. EVERY SINGLE ONE OF THESE PATENTS IS A LIE. THEY KNOW THE DRUGS DON’T WORK BETTER. THEY’RE LYING TO DOCTORS, TO PATIENTS, TO CONGRESS. AND THE MEDIA IS IN ON IT. YOU THINK THIS IS COINCIDENCE? IT’S A SYSTEM. A CORRUPT, PROFIT-DRIVEN MACHINE THAT WANTS YOU SICK AND DEPENDENT.

Shubham Dixit

India’s decision to reject Novartis’s patent was a victory for the Global South. We cannot allow Western corporations to turn medicine into a luxury. In India, we produce 80% of the world’s generic antiretrovirals. We don’t patent minor tweaks-we save lives. The U.S. system is broken because it prioritizes shareholders over sick people. This isn’t capitalism-it’s colonialism in a lab coat.

KATHRYN JOHNSON

This post is misleading. Patents incentivize innovation. Without them, no R&D. The market corrects itself. If you don't like the price, don't buy it.