For seniors with diabetes, managing blood sugar isn’t just about keeping numbers in range-it’s about staying safe. The real danger isn’t high blood sugar. It’s low blood sugar. And for older adults, even a mild dip can lead to falls, confusion, heart problems, or worse. Hypoglycemia-blood glucose below 70 mg/dL-isn’t a minor side effect. It’s a medical emergency waiting to happen, especially in people over 65. In fact, seniors experience hypoglycemia two to three times more often than younger adults. And one severe episode can increase the risk of dying within a year by 60%.

Why Seniors Are at Higher Risk

As we age, the body changes. Kidneys don’t filter drugs as well. The liver doesn’t process them as quickly. Hormones that normally kick in to raise blood sugar when it drops-like glucagon and epinephrine-become less responsive. This means when a senior takes a medication that lowers blood sugar, their body can’t fight back as effectively. Many older adults take multiple medications. On average, a diabetic senior is on nearly five prescription drugs and almost two over-the-counter ones. Some of those-like beta-blockers for high blood pressure or NSAIDs for arthritis-can hide the warning signs of low blood sugar or make diabetes drugs stronger than intended. A fast heartbeat, one of the body’s first signals of low sugar, gets masked by beta-blockers. So the person feels dizzy or weak but doesn’t realize why.Medications That Put Seniors at Risk

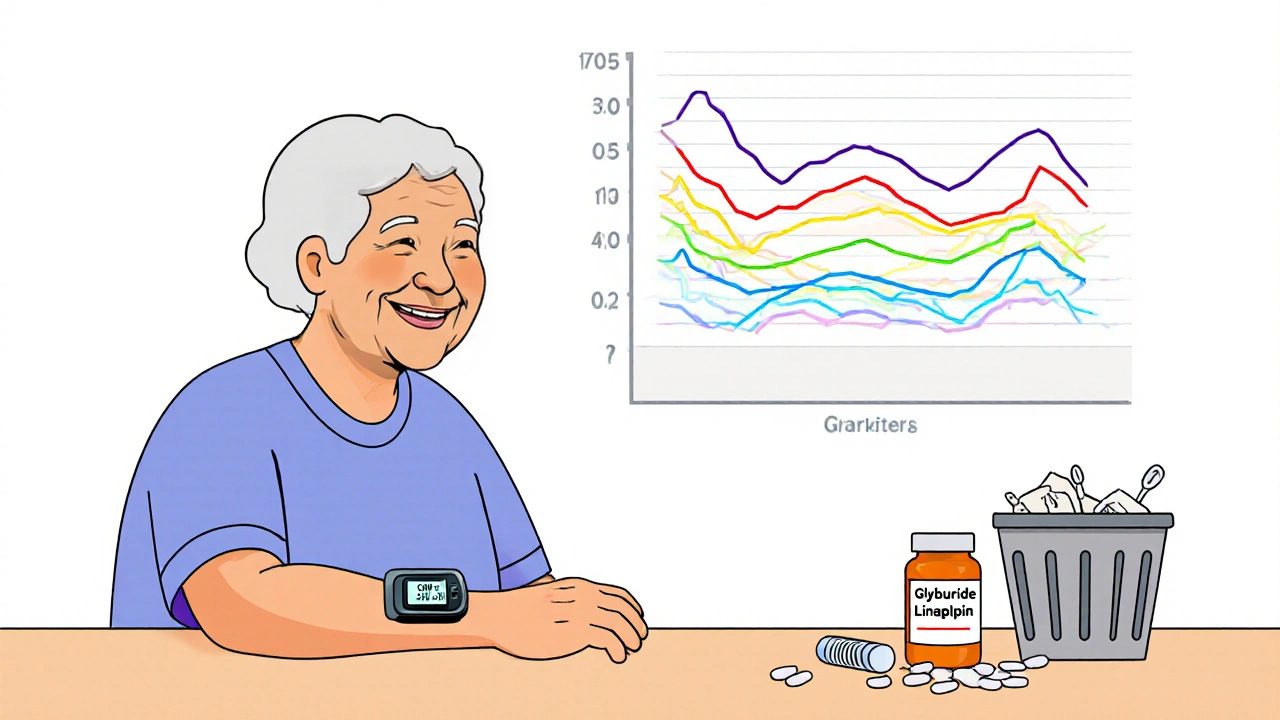

Not all diabetes drugs are created equal when it comes to safety. Some are fine. Others are dangerous for older adults. Sulfonylureas, like glyburide (Glynase), glipizide (Glucotrol), and glimepiride (Amaryl), are among the biggest culprits. These pills force the pancreas to release more insulin, no matter what your blood sugar is. That’s a problem when your body can’t adjust. Glyburide is especially risky. It sticks around in the system longer, especially if kidneys are weak. Studies show nearly 40% of seniors on glyburide have at least one hypoglycemic episode a year. That’s why the American Geriatrics Society lists it as a medication to avoid in older adults. Insulin is another major risk. It’s powerful, precise, and deadly if dosed wrong. Seniors on insulin are 30% more likely to fall due to dizziness or confusion from low blood sugar. Nighttime lows are especially common-and harder to catch. One caregiver on Reddit shared that her 82-year-old father kept waking up confused and sweaty. Switching from glipizide to linagliptin cut those episodes to zero.The Safer Alternatives

Good news: there are much safer options. DPP-4 inhibitors-like sitagliptin (Januvia), linagliptin (Tradjenta), and saxagliptin (Onglyza)-work differently. They don’t force insulin out. Instead, they help the body use its own insulin better, only when blood sugar is high. That means they rarely cause low blood sugar on their own. Clinical trials show hypoglycemia rates of just 2-5% with these drugs, compared to 15-40% with sulfonylureas. Many seniors report feeling steadier, more alert, and less afraid of falling after switching. SGLT2 inhibitors, such as empagliflozin (Jardiance) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga), help the kidneys flush out extra sugar through urine. They don’t trigger insulin release. In studies, hypoglycemia rates were only 4.5% when used alone-lower than placebo in some cases. They also offer heart and kidney benefits, which matter a lot for older adults. Metformin is still the first-line drug for many. It doesn’t cause hypoglycemia. But it’s not safe for everyone. If kidney function drops below 30 mL/min (measured by creatinine clearance), it can build up in the body and cause a rare but serious condition called lactic acidosis. Many doctors stop metformin in patients over 80 or those with even mild kidney issues. Tirzepatide (Mounjaro), a newer injectable approved in 2022, shows promise. In elderly trial participants, it caused hypoglycemia in only 1.8% of cases-far lower than insulin. It’s not yet widely used in seniors due to cost and side effects like nausea, but it’s a sign of where the field is heading.

What to Avoid

Here’s a simple rule: if a medication is on the American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria list for potentially inappropriate drugs in older adults, reconsider it. Glyburide is top of that list. Avoid it entirely. Glipizide is a little safer but still risky. Glimepiride is better than glyburide but not as safe as DPP-4 inhibitors. Don’t assume “older” means “weaker.” Some 80-year-olds are more active than 50-year-olds. But if someone has memory problems, lives alone, has trouble reading labels, or can’t recognize symptoms of low blood sugar, then the safest drug is the one that doesn’t cause low sugar at all.Monitoring and Prevention Strategies

Medication choice is only half the battle. Monitoring matters just as much. Check blood sugar regularly. The CDC recommends seniors check glucose levels before meals, at bedtime, and anytime they feel off. Keep a log. Note symptoms like dizziness, sweating, confusion, or shakiness. These aren’t “just getting older”-they’re red flags. Use continuous glucose monitors (CGMs). These small devices track sugar levels all day and night. For seniors, they’re game-changers. A 2021 study found CGM users over 65 had 65% fewer low blood sugar events than those using fingersticks. Many CGMs alert the user-and even a family member-when sugar drops too low. That’s huge for someone living alone. Teach caregivers and family. A senior might not realize they’re having a low. A spouse, child, or home health aide should know the signs: irritability, slurred speech, weakness, confusion. Keep fast-acting sugar nearby-glucose tablets, juice, or candy. Never wait for symptoms to pass. Treat low sugar fast. Get a medication review every 3-6 months. Ask your pharmacist or doctor to go through every pill, patch, and injection. Look for drug interactions. See if any meds can be stopped or swapped. Programs that include pharmacist-led reviews cut hypoglycemia-related hospital visits by nearly a third.Real Stories, Real Results

Mary Thompson, 78, had three falls in six months. Each time, she was found confused on the floor. Her blood sugar was 52 mg/dL. Her doctor switched her from glyburide to sitagliptin. In six months, no more lows. No more falls. “I finally feel like I can walk to the mailbox without worrying,” she says. On Reddit, a caregiver wrote about her father, 82, who kept waking up at 3 a.m. drenched in sweat and disoriented. Glipizide was the culprit. After switching to linagliptin, his sugars stabilized between 90 and 140. No more nighttime panic. No more ER visits. These aren’t rare cases. A 2022 study found that 62% of all diabetes-related emergency visits in seniors were due to hypoglycemia-and most came from sulfonylureas or insulin.The Bottom Line

For seniors with diabetes, the goal isn’t perfect blood sugar. It’s safe blood sugar. The American Diabetes Association says it plainly: “Avoiding hypoglycemia is a higher priority than achieving near-normal glycemia.” That means:- Avoid glyburide. Period.

- Use insulin only if absolutely necessary-and with extreme caution.

- Choose DPP-4 inhibitors or SGLT2 inhibitors first, if kidney function allows.

- Check blood sugar often. Use CGMs if possible.

- Review all meds with a pharmacist every six months.

- Teach your loved ones how to spot and treat low sugar.

What’s the safest diabetes medication for seniors?

The safest options for most seniors are DPP-4 inhibitors like sitagliptin (Januvia) or linagliptin (Tradjenta), and SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin (Jardiance). These rarely cause low blood sugar when used alone. Metformin is also safe if kidney function is normal. Avoid glyburide and other long-acting sulfonylureas-they’re linked to high hypoglycemia risk in older adults.

Can seniors take insulin safely?

Insulin can be used safely in seniors, but only with close monitoring and careful dosing. It increases fall risk by 30% due to dizziness from low blood sugar. Many doctors avoid starting insulin in older adults unless other options have failed. If used, long-acting insulin like glargine is preferred over rapid-acting types. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are strongly recommended for anyone on insulin.

Why is glyburide dangerous for older adults?

Glyburide has a long half-life and is cleared mainly by the kidneys. As kidney function declines with age, the drug builds up in the body, causing prolonged insulin release and extended low blood sugar episodes. Studies show nearly 40% of seniors on glyburide have at least one hypoglycemic event per year. The American Geriatrics Society explicitly recommends avoiding it in older adults due to its high risk of severe, life-threatening lows.

What are the early signs of low blood sugar in seniors?

Early signs include sweating, shaking, dizziness, weakness, hunger, fast heartbeat, confusion, irritability, or headache. In older adults, confusion or unusual behavior may be the only noticeable sign. Some may not feel the usual warning symptoms at all, especially if they’re on beta-blockers. Never ignore sudden changes in behavior-it could be low blood sugar.

How often should seniors have their diabetes meds reviewed?

Seniors with diabetes should have a full medication review every 3 to 6 months. This includes all prescriptions, over-the-counter drugs, and supplements. A pharmacist can spot dangerous interactions, identify high-risk medications like glyburide, and recommend safer alternatives. Programs that include pharmacist involvement reduce hypoglycemia-related hospitalizations by up to 32%.

Do continuous glucose monitors work well for elderly patients?

Yes. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are especially helpful for seniors. They track sugar levels 24/7 and alert users-and caregivers-when levels drop too low. A 2021 study showed CGM users over 65 had 65% fewer hypoglycemic events than those using fingersticks. They’re ideal for people who live alone, have memory issues, or can’t recognize low blood sugar symptoms.

giselle kate

This is why America’s healthcare system is broken. Big Pharma pushes these dangerous sulfonylureas because they’re cheap and profitable-while seniors die in their kitchens. We’ve got cutting-edge drugs like tirzepatide sitting on the shelf because insurance won’t cover them, but glyburide? Oh, it’s in every senior’s cabinet like it’s aspirin. This isn’t medicine-it’s corporate manslaughter dressed in white coats. Stop treating old people like disposable test subjects.

Amy Hutchinson

my grandma was on glyburide for 8 years and never had a problem-until the doctor switched her to Januvia and she started losing weight like crazy. now she’s always hungry and says she feels ‘floaty.’ maybe it’s not the drug, maybe it’s the doctors overcomplicating everything. i’m not saying glyburide’s perfect, but not every old person needs a ‘safer’ drug that makes them feel worse.

Archana Jha

you guys dont get it-this whole diabetes thing is a scam. the real cause of low sugar is the fluoride in the water and the 5G towers messing with your pancreas. they dont want you to know that natural remedies like cinnamon and apple cider vinegar work better than any pill. and why are they pushing CGMs? to track your data for the government. they already know your blood sugar. theyve been watching since birth. dont trust the pharma bots. go off grid. eat real food. dont take any pills. your body knows better.

Aki Jones

Let’s be precise: the data is unequivocal. Glyburide’s half-life exceeds 24 hours in patients with eGFR <60 mL/min, resulting in prolonged insulin secretion with no compensatory glucagon response-this is not ‘risk,’ it’s iatrogenic catastrophe. DPP-4 inhibitors, by contrast, modulate GLP-1 and GIP in a glucose-dependent manner, reducing hypoglycemic incidence by 80% versus sulfonylureas (OR: 0.21; 95% CI: 0.16–0.28). CGMs reduce severe hypoglycemia by 65%-per the 2021 JAMA Geriatrics RCT. This isn’t opinion. It’s meta-analysis. If your physician is still prescribing glyburide to a 75-year-old with stage 2 CKD, they’re not just negligent-they’re criminally reckless.

Sharley Agarwal

Glyburide kills. Stop it.